Permanent Professor Leadership Challenges

Within the first few years of the Academy’s founding, the framework for the academic program was created. This included defining the curriculum, building supporting facilities at the interim and permanent sites, finding academic leaders, establishing the academic structure, and hiring the faculty. The construction of the facilities at the temporary site at Lowry Air Force Base, as well as the permanent facilities near Colorado Springs, has been described elsewhere in great detail. Here we take up a discussion of some “persistent challenges”—issues that were never really “solved” but rather required continued attention and refinement over the past 60 years and will likely continue to do so into the future.

The persistent challenges we have identified are the general categories listed here:

The Leadership Team

The Permanent Professors

Faculty Organization

Faculty Composition and Development

Military/Civilian Mix

Faculty Development

Visiting Faculty

Accreditation

Institutional

Specific Disciplines

Curriculum

Core Curriculum

Modernization

Maintaining a Balance

Enhancing Cadet Performance

Within the Curriculum

Ensuring Up-to-Date Technology

Summer Programs

Graduate School

Research and Support of the Air Force

Organizing for Research

Research Centers

The Leadership Team

We begin the present story with a discussion of how the Air Force Academy faculty was organized at the top level to conduct its mission.

The Permanent Professors

In September 1959 when the Dean of the Faculty and the first Permanent Professor, Robert McDermott, was promoted to brigadier general as the first permanent Dean, the basic components of the Permanent Professor system were essentially in place. Three other Permanent Professors had been appointed in 1958 and were leading their departments: Bill Woodyard (Chemistry), Pete Moody (English), and Archie Higdon (Mechanics). Jim Wilson (Electrical Engineering) and Chris Munch (Law) would soon follow. The processes for selecting, nominating, and appointing Permanent Professors had been established: nominations from the Academy through the Air Staff and Department of Defense to the President and the Senate. And some of the finer points of the Permanent Professor system had been decided. For instance, the Academy’s request to grant sabbatical assignments for Permanent Professors had been approved by HQ USAF in May 1959.

The Academy’s seventh Permanent Professor was appointed in the Spring of 1960, Wes Posvar (Political Science), at which time there were six Permanent Professors in place and serving as Department Heads. Except for Woodyard and Higdon, all were graduates of West Point. With only 6 Permanent Professors on hand to lead 15 academic departments, General McDermott moved steadily to fill the vacancies. His goal was to identify the most promising, academically qualified officers for their long-term leadership potential, which often meant selecting younger men rather than the traditional appointment of the most senior officer in the unit. General McDermott moved deliberately, and in the following year three new Permanent Professors were appointed: Wil Ruenheck (History), Al Miele (Foreign Languages), and Wayne Yeoman (Economics).

The Academy’s seventh Permanent Professor was appointed in the Spring of 1960, Wes Posvar (Political Science), at which time there were six Permanent Professors in place and serving as Department Heads. Except for Woodyard and Higdon, all were graduates of West Point. With only 6 Permanent Professors on hand to lead 15 academic departments, General McDermott moved steadily to fill the vacancies. His goal was to identify the most promising, academically qualified officers for their long-term leadership potential, which often meant selecting younger men rather than the traditional appointment of the most senior officer in the unit. General McDermott moved deliberately, and in the following year three new Permanent Professors were appointed: Wil Ruenheck (History), Al Miele (Foreign Languages), and Wayne Yeoman (Economics).

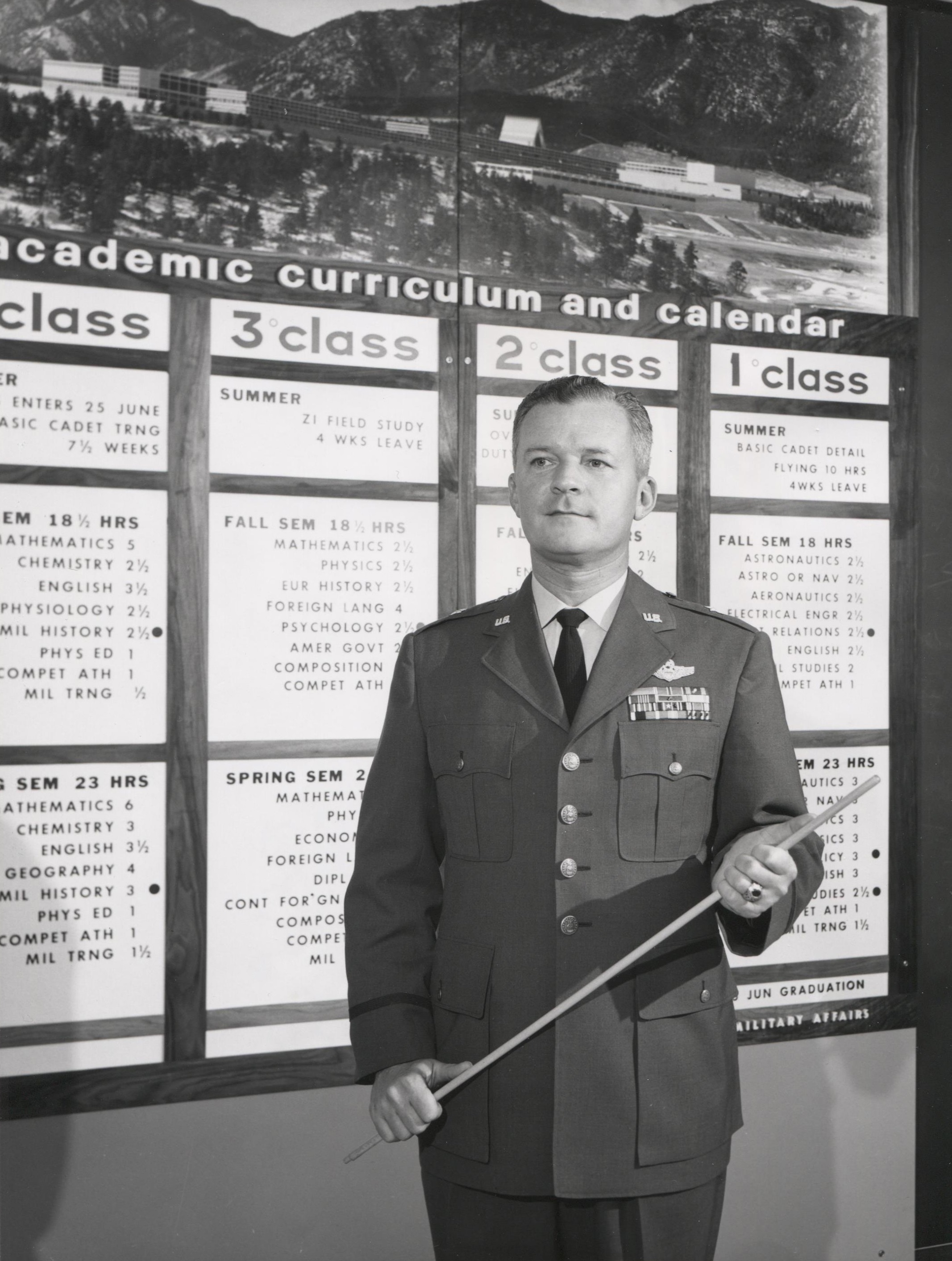

The photograph here shows the three new appointees, Ruenheck, Miele, and Yeoman, taking the oath of office from General McDermott, on October 24, 1961, while the Academy Superintendent, Major General William S. Stone, looks on.

In 1962 two more Permanent Professors were appointed, George Fagan (Cadet Library) and Roger Bate (Astronautics). Then in 1964, three more officers were appointed as Permanent Professors: Phil Erdle (Mechanics), Ron Thomas (Electrical Engineering), and Mal Wakin (Philosophy). However, these three officers were quite junior in rank; they were Permanent Professors as lieutenant colonels, but they did not assume positions as Department Heads for another year or more. Mal Wakin was the most junior; he was Captain Wakin when appointed and Lieutenant Colonel Wakin the next day! The goal was to fill all 22 of the authorized Permanent Professor positions as soon as practical. In 1966 another four officers were appointed Permanent Professors: Gil Taylor (Geography), Jesse Gatlin (English), John Mione (Physics), and Al Hurley (History). And in 1967 another four: Em Fluhr (Civil Engineering), Mark Kinevan (Law), Pete Carter (Life Sciences), and Dan Daley (Aeronautics).

At the same time, Permanent Professors were beginning to retire. The first to retire was Jim Wilson, who retired in 1965 (as a brigadier general). Pete Moody and Archie Higdon followed in 1967. Thus, the Permanent Professor dynamic had run its full cycle, from appointment to service to retirement. By the late 1960s, the Permanent Professor program had approached a steady-state condition, namely that searches were mostly for the successors to the original appointees. Of course, that is the situation to this day, where most academic departments have seen four, five, or six Permanent Professors. Actually, the 84 Permanent Professors presently on the retired roster have a cumulative 983 years of service in the positions, for an average of about 12 years each.

A pair of interesting developments almost came to pass in 1966. HQ USAF invited the Academy to consider whether the number of Permanent Professors should be increased, especially in light of the increase in the strength of the Cadet Wing from 2,800 to 4,417. The Dean and Superintendent argued that an increase from 22 to 40 Permanent Professors would be appropriate (the target of 40 authorizations was later reduced to 30). The reasoning for the increase was, in part, that some departments (viz., English and Mathematics) had grown large enough to warrant dividing, many Permanent Professors were away for extended periods (on sabbaticals), and highly important staff positions should be filled full-time by Permanent Professors (e.g., Assistant Dean for Graduate Programs, Assistant Dean for Research, etc.). At the same time, the Academy prepared a proposal to increase the pay of Permanent Professors, based on comparisons with pay of senior professors at universities. Although there already was a modest additional pay of $250 per month for Permanent Professors with more than 36 years of service, it was argued a pay increase was needed as an incentive for Permanent Professors to stay until age 64. Both of these actions, increase in number and increase in pay, would have required a change to Public Law. Despite some support from the Academy’s Board of Visitors, neither action was endorsed by the Air Staff and both issues were dropped; neither has been seriously raised again. With these initiatives set aside, the Permanent Professor system reached its maturity by 1967. All the elements were in place upon which to build for the generations to come.

Faculty Organization

Academic Departments and Divisions. During the first year at the interim Academy site, the Dean of the Faculty organized the academic body into seven academic departments: English and Foreign Languages; History; Human Relations (Law, Geography, Philosophy, Psychology); Economics and Government; Mathematics; Chemistry, Physics and Electrical Engineering; and Applied Sciences (Mechanics and Materials, Graphics, Thermodynamics, Aerodynamics). A year later, in August 1956, as the faculty and curriculum were filling out to meet the need for sophomore courses, some new departments were created and then further organized into Academic Divisions.

The four academic divisions were Humanities, Social Sciences, Basic Sciences, and Applied Sciences. A Division Chairman was named for each division. The academic divisions gathered departments of similar academic disciplines to provide mutual support as well as to better coordinate curriculum planning in addition to course integration and development. The Division Chair is a coordinator, not a director, and the sole role is one of leadership in academic matters; the Chair has no supervisory or administrative authority over other departments or courses.

At this time, the leader of each department was officially appointed as a Department Head, where the title was changed from “Chair” to “Head” to emphasize the distinction between the duties of the chair of a civilian academic department and those of the leader of a military unit. The Department Head encompassed not only the academic duties of the chair but also the responsibilities associated with military command. Appendix B includes a breakdown of the duties of the Department Heads and Division Chairs.

Vice Dean of the Faculty. In addition to the academic departments and divisions, the first Dean of the Faculty organized a staff function, which included a Vice Dean, a Deputy Dean, and several support directorates. Colonel Robert F. McDermott was appointed Vice Dean in 1954 and continued as Vice Dean until appointed the Acting Dean in 1956. Subsequently, the position of Vice Dean was abolished for 10 years. Before 1965, some of these duties were handled by an Associate Dean for Academic Affairs, Colonel Jim Wilson. When Jim Wilson retired in 1965 the duties were generally divided between an Associate Dean for Humanities and Social Sciences (Colonel Pete Moody), an Associate Dean for Engineering and Basic Sciences (Colonel Archie Higdon), and an Associate Dean for Educational Services (Colonel Winston Fowler). The reorganization in 1966 established a single position of Vice Dean of the Faculty; Colonel Pete Moody was the first to occupy the position. Since then, the Vice Dean of the Faculty has always been one of the Permanent Professors, who was detailed into the position from their department. A list of the Vice Deans is in Appendix B.

The duties of the Vice Dean of the Faculty are essentially those of a Chief of Staff: to lead the faculty organization in the absence of the Dean, to provide advice to the Dean on all Academy matters, and to supervise the faculty staff agencies. The principal staff agencies supporting the academic mission are Research, Registrar and Student Academic Affairs, Educational Innovation, Cadet Library, and International Programs. These are briefly described in Appendix B.

In 2018 the Dean, Brigadier General Armacost, elected to use the unfilled 23rd Permanent Professor authorization to establish a new staff office, “Vice Dean for Strategy and Curriculum.” This became a second Vice Dean, for the traditional Vice Dean of the Faculty position was retained. Effective in the summer of 2018, Colonel Gary Packard was appointed Vice Dean for Strategy and Curriculum and Colonel Troy Harting the Vice Dean of the Faculty. Gary Packard’s position was permanent in the sense he would not return to the Department of Behavioral Sciences and Leadership (a new Permanent Professor is to be appointed there).

Dean of the Faculty. The Dean of the Faculty has the ultimate responsibility for properly administering the academic program. But the Dean shares the authority over academics with the Department Heads, the Faculty Council, the Curriculum Committee, and the Academy Board. The Dean, within policies prescribed by the Superintendent and in consultation with the Permanent Professors, establishes academic policies on organization, curriculum development, scheduling, instructional workloads and standards, and personnel. The Dean is responsible for monitoring the instructional activities of the departments and is the first-line supervisor of each Department Head to whom are delegated virtually all authority for the day-to-day operations of the academic program. In consultation with the Superintendent, the Dean appoints Division Chairs, Department Heads, and chairs of ad hoc committees. The Dean frequently interacts with the Commandant of Cadets, the Director of Athletics, and the Superintendent to identify and coordinate the resolution of issues or the pursuit of opportunities that may arise. The Dean is often the face of the faculty to the Board of Visitors, the charitable organizations supporting the Academy, and distinguished visitors to the Academy. The Dean frequently travels to speak to Academy alumni chapters or parents’ clubs across the country and is the Executive Agent for the Academy Board.

The Academy Board. The first Academy Board was formed by General Harmon in September 1955 with 6 of the 11 members being faculty. HQ USAF formally established the Air Force Academy Board on January 20, 1956, to consist of the Superintendent, Dean, Commandant, and heads of academic and airmanship departments as appointed by the Superintendent. The Board is the Academy’s senior advisory body, chaired by the Superintendent. In its current configuration, the 12 voting members of the Academy Board are the Superintendent, Vice Superintendent, Commandant of Cadets, Dean of the Faculty, Director of Athletics, the four academic division chairs, Director of Athletic Programs/Physical Education, Vice Commandant, and a Member-at-Large (appointed by the Superintendent). The Board provides advice regarding virtually all aspects of the cadet program. It advises on the selection of each entering cadet and the disposition of deficient cadets (retention or disenrollment). The Board also advises on the academic, military, and physical requirements for graduation and the standards by which cadets are measured, as well as recommending those who meet the requirements for graduation and commissioning. In particular, the Academy Board establishes the academic curriculum (the Curriculum Committee is a standing committee of the Academy Board) for approval by the Superintendent.

Faculty Composition and Development

Military/Civilian Mix

Discussions of the faculty composition—whether all military or a military/civilian mix—took place from the beginning of planning for the Academy. There was agreement that faculty in the sciences and engineering disciplines should be military, where the service had a strong base. However, the Air Academy Planning Group and the first Dean, General Zimmerman, preferred to have civilians in the humanities and social sciences. Colonel McDermott, as the Vice Dean, argued persuasively for an all-military faculty and convinced both General Zimmerman and General Harmon to follow that model.

In the summer of 1957 HQ USAF raised the issue again and requested the Academy consider adding civilians to the faculty, but the Superintendent and Dean decided to maintain the all-military position. General McDermott enumerated five reasons why the Air Force Academy should have an all-military faculty (The Composition of the AFA Faculty, September 1957):

1. The Air Force can provide a quality faculty from its own ranks. Air Force officers represent a cross-section of all professions with many thousands of academic degrees and experience in research, management, politico-economics, and teaching.

2. The feasibility of obtaining a qualified civilian faculty is questionable. Due to the remoteness of the Academy and its limited programs, first-rate faculty would gravitate toward bigger universities where they would receive more recognition.

3. High teaching standards are better maintained with a military faculty. Contrary to practices in civilian institutions, military supervisors would visit classrooms, evaluate teaching, and enforce standards of performance.

4. A military faculty motivates a cadet to an Air Force career. The only tangible device to achieve this is to place the best possible officer before the cadets for all four years.

5. A military faculty provides a long-term gain for the Air Force. The knowledge gained by young officers in graduate school and teaching at the Academy would provide better service when they returned to their career field.

These arguments were powerful at the time, and they effectively settled the question in favor of preserving the all-military faculty, at least temporarily.

It is interesting to note whether these arguments retain their strength after the passage of 60 years and from a position of already having added a significant civilian component to the faculty. The first point remains sound—there is a wealth of talent across the Air Force. However, in recent years certain academic fields, the humanities in particular, have struggled to find qualified officer-instructors. Other factors affecting the argument are that AF manning priorities have changed and that the current high operations tempo restricts who can be released for faculty assignments.

The second argument, that it was questionable whether the Academy could attract quality civilians, may have been the case in the 1950s, but the Academy is now adjacent to a large community with much to attract an educated populous. Moreover, the actual experience in hiring quality civilians for the faculty has been very positive. To the third point, the majority of civilians brought on board have readily adapted to the Academy way of mentoring. Both civilians and military go through the same new instructor training, welcome classroom visits by department leadership, and buy into the Air Force team approach.

The fourth argument, about officers being the best role models for cadets, continued to be made years later. Here is how General Woodyard reiterated the point (Faculty Operating Instruction No. 30-4, Faculty Selection, February 1, 1969):

One key to Academy mission accomplishment is the quality of instructors on the all-military faculty. In his four years at the Academy a cadet spends more hours under closer supervision receiving instruction as a student in a small academic section than he does in any other supervised activity. In this learning situation the instructor teaches not only by what he says but also by who he is. His job is not merely to transmit knowledge but also to impart the qualities of leadership required of an officer in the United States Air Force. The hallmarks of leadership in the military profession are the highest standards of personal integrity, devotion to duty, and dedication to the service of the nation. These ideals are not self-generated; they must be imparted. They can be imparted only by those in frequent contact with the cadets and only to the extent that the instructor is a living example of these ideals. This explains not only why we have an all-military faculty but also why only the finest officers should be privileged to serve on it.

Few would disagree that cadets must be exposed to many officer role models. However, civilians can be good role models, too—role models of citizenship and role models of excellence in many areas.

The final argument from General McDermott’s list continues to be reiterated by present-day Permanent Professors when they speak of the Academy’s second graduating class—the large group of officers who each year complete their faculty tours and return to the “big Air Force.” They take with them valuable experiences and additional insights from their Academy exposure.

The issue of adding civilians to the Academy faculty resurfaced in 1975–1976 and again in 1992, as described more fully in Appendix C. The 1975 economic analysis by the General Accounting Office and a study on educational excellence by the Department of Defense (by the “Clements Committee”), urged adding civilians at the 5 to 10 percent level. However, the issue was effectively set aside again, in part because the Academy had begun a new Distinguished Visiting Professor Program. Finally, in 1992 a congressional initiative demanded an aggressive civilianization program, and the Secretary of the Air Force responded that the Academy would move toward a goal of 50 percent civilian faculty as quickly as possible.

The Dean formed a working group to develop a program to implement the civilianization effort. The effort was led by Colonel Jim Head, Permanent Professor of Physics. Despite much initial resistance from some, the Permanent Professors outlined the main features of what they believed were essential elements of a successful civilian faculty program. A key issue was no lifetime tenure, as was common in universities and colleges. Rather, the civilians should have term appointments, renewable, much as the military faculty. Next, the faculty wanted great flexibility with position descriptions, review and selection of candidates, and appropriate control over hiring and salary decisions—in short, not the standard Federal government civil servant General Schedule classification and pay system. Colonel Head’s team developed the policies and procedures to permit hiring and paying civilian faculty members under an excepted civil service authority similar to that at Air University and the Air Force Institute of Technology. In December 1992, the Superintendent submitted the Academy’s plan to go to about 25 percent civilians by 2000 and pause there to evaluate the next phase. The AF Chief of Staff approved the plan, which was provided to Congress in March 1993.

The Civilian Faculty Plan went forward aggressively, with 14 positions advertised for Academic Year 1993–1994, expanded across all academic departments by the fall of 1994, and built steadily to about 25 percent by 2000 (numbers include visiting faculty, normally about 5 percent of total). The program spread across all academic departments, bringing additional disciplinary expertise as well as a more diverse hiring pool. Moreover, the option of hiring civilians brought relief from some of the persistent challenges of military faculty staffing. On many occasions, a temporary military shortfall could be overcome by the availability of a short-term temporary civilian hired for a semester or a year. On other occasions, constant military shortfalls (either in hard-to-fill academic areas or highly stressed military fields) were overcome by permanent military-to-civilian conversions. The overall assessment at the time of the pause in 2000 was that civilians had been a net enhancement for the Academy.

After the target of 25 percent civilians was reached, the civilian faculty numbers continued to grow slowly. The main impetus for the growth of the civilian faculty was the difficulty in filling military faculty positions, especially for rated officers. At the start of the 2017–2018 academic year, the civilian faculty proportion of the total authorized teaching faculty had grown to about 36 percent. Another round of 46 military-to-civilian faculty conversions in 2018 brought the civilian component to 40 percent of the teaching faculty.

Initially the goal was to have 60 percent rated personnel on the Academy faculty; this was later reduced to 50 percent. From the inception the rated officer target was challenging, but rated officers were available for assignment to non-flying duties. By the late 1960s, when the Air Force was at war in Southeast Asia, the Academy experienced increased difficulty in attaining its goal. For rated officers, more than non-rated, a faculty assignment can be regarded as an interruption to their career progression. This is especially true if it has to be preceded by graduate school. Add in the staffing shortages and operational demands in flying fields, and the Academy frequently has had rated faculty positions vacant. Consequently, most of the 46 military-to-civilian conversions for 2018 involved the elimination of a (vacant) rated position in favor of a civilian position that can be filled.

Faculty Development

New Faculty Orientation and Instructor Training. The salient feature of the Academy faculty is rapid turnover of the junior military instructors who come for three or four years and return to the Air Force. During the years of the all-military faculty, this group might have amounted to 100–150 new instructors every year. At present, with a sizable civilian faculty, the number of new military faculty members is reduced, but there is a steady stream of newly hired civilians, some of whom also have little teaching experience. Regardless of their teaching experience, both officers and civilians who are “new” to the Academy face the challenge of understanding the institution in which they are going to work. Recognizing these needs, the Dean organized a New Faculty Orientation, and departments conducted New Instructor Training programs.

From at least 1960 to the present, it has been expected that all newly assigned (and returning) faculty attend a New Faculty Orientation program. The purpose is to ensure all personnel understand the mission of the Academy and to explain the facets of the Academy that are unique. Typically, the orientation includes briefings by the Dean and representatives from the Superintendent, Commandant, and Athletic Director. It features presentations on the Cadet Wing, the Honor System, curriculum, scheduling, the library, as well as classroom standards, best teaching practices, and student services.

In addition, each academic department has a training program for new instructors. It is a major team-building activity as well as the best opportunity to impart the key responsibilities, department policies, procedures, standards, and expectations to the new and returning faculty. Experienced faculty can demonstrate lesson planning and appropriate educational pedagogy. New faculty give practice lessons, under supervision, in regular classroom conditions. This is an extremely valuable investment made by each department involving the direct participation of the Permanent Professor/Department Head and many of the department’s other senior faculty. Two prominent features of the Academy system, core courses and small class sizes, make this training especially vital.

Tenure. The turnover of military faculty has a downside in that much of the valuable experience they take with them is lost from the Academy. Therefore, a program was instituted in 1964 to ensure some military officers besides the Permanent Professors would be available for extended faculty duty to help sustain continuity in the academic programs. This was the Tenure Associate Professor Program. A limited number of officers, majors and lieutenant colonels, would be authorized to remain on the faculty beyond their initial assignment on renewable four-year tours. The target was for 10 percent of the faculty to be “tenured” (in addition to the Permanent Professors). The increased stability helped sustain the goal of at least 25 percent doctoral degrees on the faculty and enhance accreditation efforts. Tenure associate professors and tenure professors were later called sequential tour officers to more precisely describe the limited nature of their appointments. In 2009 the program was redefined as the Senior Military Faculty (SMF) Program. Officers selected for SMF status, lieutenant colonels and senior majors (by exception), are expected to remain current in their operational discipline by taking yearlong “re-bluing” assignments every five years or so. The combination of Permanent Professors and SMF positions is currently limited to 15 percent of authorized USAFA faculty strength.

Sabbaticals. The sabbatical program at the Academy developed as the number of senior faculty increased. In higher education the term “sabbatical” has come to mean any extended absence in the career of a professor for a specific purpose, say writing a book or traveling for research. At the Air Force Academy, the term also can mean increasing or updating professional military experience. Sabbaticals were authorized for Permanent Professors beginning in 1959, for tenure professors and tenure associate professors in 1966, and, since 1993, for civilian professors and associate professors.

By the early 1960s many of the Academy military faculty members were encouraged to plan for sabbatical assignments. The normal expectation was that one might have a sabbatical after four years of continuous faculty service, and that additional sabbaticals might be authorized every five to seven years thereafter. Some tension developed over the desire for Permanent Professors to take an assignment for “military reorientation” versus the traditional sabbatical assignment. The 1968 Board of Visitors expressed the opinion that reassignment to military duties should not be considered a sabbatical in the accepted academic sense. The distinction between the two types of assignments was clear, but both came to be known as sabbaticals. In sum, Permanent Professors, along with other senior faculty members, were permitted and encouraged to take sabbatical assignments, and almost anything they could imagine would fit under one category or the other.

For the most part, Permanent Professors took few purely academic sabbaticals, but there were some. Pete Moody took a sabbatical to Cambridge University, 1961–1963, where he earned his Doctorate. Wes Posvar was at Harvard, 1962–1964, also earning his PhD. However, there were many who took sabbaticals to military units with a strong academic component. As an example, Bill Woodyard left the Chemistry Department to attend the Industrial College of the Armed Forces in 1961. He later had a tour in Brussels with the European Office of Aerospace Research, 1965–1967, which set up a series of sabbaticals to that office for Permanent Professors in the sciences and engineering, including John Mione, Bob Lamb, Cary Fisher, and Ron Reed.

On the side of a military sabbatical with an academic flavor, Al Hurley initiated and participated in a program to engage Academy officers in supporting the war in Southeast Asia, known throughout the Air Force as Project CHECO (Contemporary Historical Evaluation of Combat Operations). From 1968–1972 many Academy officers went to Vietnam and produced over 100 classified studies of the war, researched and written on the scene and drawing on their training to gather information, analyze data, and write clearly. Several Permanent Professors from the humanities participated in Project CHECO, including Carl Reddel and Jesse Gatlin. Dick Rosser was on sabbatical in London, 1969–1971, doing research at the International Institute of Strategic Studies and attending the British Imperial Defence College. General McDermott, while Dean, took a year, 1964–1965, to be on the faculty at Air University. Mike DeLorenzo was Vice Commander, Air Force Research Laboratory, 2001–2003. Bob Giffen was the US Air Attaché to Germany, 1986–1987.

There later developed the concept of an “internal sabbatical,” which was an assignment at the Academy, but outside one’s department. Prime examples are the many Permanent Professors who left their departments for a year or two while serving as Vice Deans of the Faculty. Another is Jim Woody who was the Vice Commandant of Cadets for two years. Yet another example is Randy Cubero, who took an internal sabbatical to explore the concept of public-private partnership in developing videodiscs for foreign language learning, sharing technology and profits through a Cooperative Research and Development Agreement. Another is Greg Seely, who for 18 months led the Academy’s Installations Directorate.

Visiting Faculty

Distinguished Visiting Professors(DVPs). A program to bring a few prominent civilian professors to the Academy for yearlong visits was initiated for Academic Year 1975–1976 in response to the issues raised by the Clements Committee (see above). The DVP Program grew slowly; by 1985–1986, there were six DVPs on board. Over time, the emphasis and character of the program changed, due largely to budgetary restrictions and partly to the difficulty of attracting the kind of high-level visitors the program initially intended. The Visiting Faculty Program, as it is now called, includes 20 or so visitors each year, nominally one per academic department.

Endowed Chairs. Brigadier General Philip J. Erdle, Permanent Professor, retired, formed the Academy Research and Development Institute (ARDI) in 1984 with the goal of establishing an endowed chair in each USAFA academic department; to date ARDI has endowed eight chairs. Beginning in 2007, the USAFA Endowment has endowed chairs for the Center for Character and Leadership Development. Some details of these endowed chairs are in Appendix C.

Military Officer Exchange Program. Colonel Al Miele, Permanent Professor and Head of Foreign Languages, is credited with initiating the foreign officer exchange program, which brought allied officers as language instructors and provided authenticity and cultural value to enhance the Academy’s courses. The exchanges began in the 1960–1961 academic year, with an officer from Peru and one from West Germany, and rapidly expanded in the years that followed. By the time of Colonel Miele’s retirement in 1968, the program had included officers from Argentina, Belgium, Bolivia, Chile, France, Germany, Mexico, Peru, Republic of China, and Spain. There were also exchanges of officers from English-speaking countries—Australia, Canada, and the United Kingdom—who taught military training, navigation, and Political Science. The exchange program has ebbed and flowed over the years, subject to manpower policies and funding. For 2017–2018, the list includes Brazil, Germany, Spain, France (in Aeronautics), Korea (in Engineering Mechanics), and Japan (in Military and Strategic Studies).

Accreditation

Institutional Accreditation

Beginning with the first detailed planning for the Air Force Academy in 1948, accreditation always had been an important requirement. Legislative law required West Point and Annapolis to have accreditation in order to grant degrees. It was assumed this provision of the law would be applied to the AF Academy as well. In 1957 Colonel Woodyard, Professor and Head of Chemistry, was appointed by the Superintendent to chair an Accreditation Steering Committee to prepare a self-study required for use by the regional accrediting agency, the North Central Association of Colleges and Schools (NCA). (The group’s work to deliver the report by July of 1958 is detailed in Chapter 1.) The accreditation evaluators’ report recommending the unusual accreditation of the Academy in April 1959 before its first class had graduated stated: “[M]ission is clear, well understood and supported by all” and “… esprit de corps developed in less than four years is… a great tribute to the military and educational leadership of the Academy.” The evaluators were “…surprised and gratified that the Air Force Academy places great emphasis on a broad program of general education.” They praised the evenly divided attention given to basic and applied sciences and humanities and social science. They saw the need for better accounting practices, for a field house and on-base flying facility, and increased faculty competence as measured by a higher percentage of faculty PhDs who were more evenly distributed among disciplines. However, the latter concern was mitigated in their view by the many officers in the pipeline pursuing PhDs, new faculty orientation and enthusiasm, detailed lesson plans, close senior faculty oversight, and finally by the “…high caliber of the faculty as human beings and military officers.” The Academy was granted the maximum accreditation. Although there would be concerns raised in subsequent accreditation evaluations about cadet and faculty workloads, cadet and faculty diversity, faculty research, and available funding, the Academy has always been granted the maximum accreditation term. Each of the five subsequent successful Accreditation Steering Committees has been chaired by a Permanent Professor, as is the current self-study, led by Colonel Dan Uribe, Head of the Department of Foreign Languages. It should be noted that while the bulk of the preparation involves the faculty, there are significant portions of the self-study data that must be obtained from virtually all Academy organizations. More information on .these self-study and accreditation reports can be found in Appendix D. A good example of the continuing commitment of Permanent Professors to higher education is retired Permanent Professor Cary Fisher, who was recently elected as a Public Member of the Higher Learning Commission Board of Trustees, the NCA’s successor organization.

Accreditation of Specific Disciplines

Most academic disciplines have national societies or associations formed for the mutual benefit of educators in those subjects. Some of these have seen the need to provide accreditation of specific degree programs to identify those institutions who meet applicable quality standards. It is desirable for the Academy to seek and achieve accreditation in disciplines where it is available. The Air Force requires accredited degrees for graduates to work in some engineering disciplines.

Engineering Programs. As soon as the Engineering Sciences major was approved by the Academy Board in 1958, the Permanent Professors in the Engineering Division actively sought accreditation by the Engineering Council for Professional Development (ECPD). The ECPD was founded in 1932 by seven engineering societies and began accrediting engineering programs in 1936. In 1980 the ECPD was renamed the Accreditation Board for Engineering and Technology (ABET) to more accurately describe their emphasis on accreditation. Currently, ABET is supported by 35 professional societies who set standards and provide experts to serve as evaluators. Under the vigorous leadership of Permanent Professor #4, Archie Higdon, the Academy prepared a self-study report and then hosted an evaluation visit. In October 1962 the Engineering Sciences major was accredited. In October 1967 the newly established degree programs in Aeronautical Engineering, Civil Engineering, Electrical Engineering, and Engineering Mechanics were granted initial accreditation, and the Engineering Sciences major was reaccredited. All were for the maximum term. Astronautical Engineering was added to the list of accredited engineering programs when the others were reaccredited in 1973. In 1979 the General Engineering (Divisional) major was accredited, which allowed cadets having problems in a disciplinary engineering major or seeking a broader engineering education to earn an accredited engineering degree. In the following years additional programs were accredited: Mechanical Engineering (1991), Environment Engineering (1997), Computer Engineering (2003), and Systems Engineering (2009). In the nine evaluations following the one in 1962, ABET has accredited all programs for the maximum term, many for several years retroactively. A steering committee of the engineering Permanent Professors, headed up by the Chair of the Engineering Division, has managed the preparation of the self-studies and the evaluation visits. The next ABET evaluation visit will be in 2021. Additional detail on the evaluation findings for each evaluation visit and the leadership provided by the Permanent Professors can be found in Appendix D.

It is interesting to note that several engineering Permanent Professors as well as many other engineering faculty members have devoted much volunteer time over many years to assist, literally worldwide, in the accreditation process. Permanent Professor Cary Fisher has evaluated over 40 Engineering programs. The example provided by Ron Thomas, Permanent Professor and Head, Department of Electrical Engineering, led two former Air Force Academy Electrical Engineering faculty members who retired as USAF lieutenant colonels to work full-time for ABET. Dr. George Peterson served as the Executive Director of ABET for 15 years. George was succeeded in 2009 by Dr. Michael Milligan, who is currently Chief Executive Officer and Executive Director of ABET. Ron also performed numerous evaluation visits and was honored in 1992 as an ABET Fellow for his accreditation leadership.

Computer Science Programs. In response to the anticipated boom in computer science education, ABET helped establish the Computing Sciences Accreditation Board (CSAB) in 1985. That year the Academy’s Computer Science program was the first in the nation to be visited for evaluation and was granted accreditation. CSAB merged with ABET in October 2001, and the Computing Accreditation Commission of ABET now accredits Computer Science and related programs. The Academy’s Department of Computer Science was renamed Computer and Cyber Sciences in 2017 to reflect the increasing emphasis on cyber operations, and it was administratively moved to the Engineering Division. Consequently, the accreditation cycle for the programs in Computer Science and Computer and Network Security (accredited for 2016) has been synchronized with that of the Academy’s engineering programs.

As Department Head for Computer Science, Permanent Professor Bill Richardson worked vigorously to modernize and formalize the discipline at the Academy and across the nation. He was ultimately named Chairman of the Computer Science Accreditation Board. He was honored as a CSAB Fellow for his leadership in the early years of Computer Science as it grew into a widely recognized academic discipline. Retired Permanent Professor Hoot Gibson currently serves on the Executive Committee of ABET’s Computing Accreditation Commission, and retired Lieutenant Colonel Larry Jones, inspired by Bill Richadson, served as ABET President, 2014–2015.

Chemistry. The American Chemical Society (ACS) accredits the Academy’s Chemistry, Biochemistry, and Materials Chemistry options taught by the Department of Chemistry. The first accreditation for Chemistry in November 1967 was due to the efforts of Permanent Professor and Head, Department of Chemistry, Bill Woodyard. The Department of Chemistry has maintained accreditation (now called approval for certification) ever since by submitting an annual report with a periodic report due every six years to the ACS Committee on Professional Training. A site visit may be requested by the Committee.

Management. Permanent Professor Rita Jordan led the effort that in 2001 gained the initial accreditation for the Management major by the Association to Advance Collegiate Schools of Business (AACSB). Air Force was the first service academy to gain this accreditation. The Management Department has maintained this accreditation by completing a continuous improvement review process that includes a self-study and evaluation visit every five years.

National Collegiate Athletic Association Certification

The NCAA certifies higher education athletic programs to ensure integrity in the institution’s athletics program and compliance with NCAA rules and regulations as well as to help athletic departments improve. NCAA legislation mandating athletics certification was adopted by members in 1993. The certification process required a self-study by the institution that covered governance and commitment to rules compliance, academic integrity, gender/diversity issues, and student athlete well-being. After reviewing the self-study, the NCAA performed a site visit with the results of study review and visit reported to the NCAA Committee on Athletics Certification. The first Academy Self-Study Steering Committee was chaired by Permanent Professor Bob Giffen in 1989; the second study was led by Permanent Professor Hans Mueh in 1999. Permanent Professor Tom Yoder chaired the third one in 2009 with certification received in March 2011. The current NCAA process requires an annual report that the Athletics Department’s Compliance Office provides. No other reports or visits are required as long as an institution remains in compliance.

Curriculum and Curriculum Changes

Chapter 1 describes the development of the curriculum up through the approval of academic majors for the Classes of 1959 and 1960. This section provides a short recap and goes on to describe major curricular changes in the ensuing years. The next section describes some other initiatives intended to enhance the cadets’ opportunities to excel.

The Permanent Professors bear the major burden of maintaining an academic curriculum to meet the needs of the Air Force and maintain accreditation. In addition, the overall academic workload must be managed within the total demands on a cadet’s time, which also include military training, physical education, sports, and military leadership roles within the Cadet Wing. The core curriculum is designed to prepare all cadets for a lifetime of dedicated service to the nation. The Professors also must design, deliver, and maintain relevant major courses of study that meet the Air Force’s needs and are meaningful to the cadets. Balancing the academic demands of a specialized field of study with the broad educational objectives of the core is a persistent challenge. While this section only describes major changes in the curriculum, it is of interest that the Curriculum Committee, whose membership is more than 80 percent Permanent Professors, considers well over 100 proposed changes to the curriculum every year. Each is carefully analyzed to ensure that the potential impact on the core, individual majors, and cadet workload is acceptable.

Core Curriculum

The core curriculum “is rooted in the best traditions of the past, taught in the context of the present, and continually reexamined in the light of the future needs of the Air Force.”

—Maj Gen James E. Briggs, USAFA 2nd Superintendent

The prescribed curriculum approved on April 29, 1954, for the first class of cadets had nearly equal semester hours of social sciences and humanities when compared to those for basic sciences and engineering. This balance has been a key feature in the core curriculum since early planning began in 1948 and still remains so. This principle has been reaffirmed and validated by each of the many external reviews conducted since 1949. The first cadets that entered in the summer of 1955 faced a completely prescribed curriculum, but as explained in this section, much flexibility has been introduced to interest and challenge the cadets while still ensuring that all graduates meet common core educational learning objectives, now called learning outcomes.

The prescribed curriculum approved on April 29, 1954, for the first class of cadets had nearly equal semester hours of social sciences and humanities when compared to those for basic sciences and engineering. This balance has been a key feature in the core curriculum since early planning began in 1948 and still remains so. This principle has been reaffirmed and validated by each of the many external reviews conducted since 1949. The first cadets that entered in the summer of 1955 faced a completely prescribed curriculum, but as explained in this section, much flexibility has been introduced to interest and challenge the cadets while still ensuring that all graduates meet common core educational learning objectives, now called learning outcomes.

The rigidity of this first curriculum is illustrated in the photo to the right showing the Dean of the Faculty, Brigadier General McDermott, before a permanent display of the curriculum. This initial lack of flexibility soon changed, but the balance in the core has remained. One measure of the maturation of the curriculum is that the USAFA Catalog completely describing the application, appointment, and entrance testing as well as the curriculum for Academic Year 1955–1956 was 51 pages, whereas the 2017–2018 Curriculum Handbook describing only the curriculum and associated procedures is now 386 pages.

There was an almost overwhelming emphasis on refining the curriculum in the early years. For example, there were three major changes to the curriculum during the first year of classes, Academic Year 1955–1956. The external Academy Curriculum Review Board comprising general officers and chaired by Major General Briggs that met in February 1956 recommended one of these changes. After reviewing the Board’s recommendations, the faculty changed the semester hours for eleven courses and added two courses, a 2-semester-hour course in Aircraft Design Appreciation and 10 semester hours of foreign language (French or Spanish).

However, in 1957 General Briggs, now the Superintendent, cautioned the members of the Academy Board that it was time to stop listening to outside reviewers and let the curriculum stabilize. Changes still occurred, though, with the elimination of the core navigation program with the Class of 1961 and the May term that had been devoted to military training. At the same time navigation training was moved to the Dean of the Faculty as was the Commandant’s classroom leadership training, which resolved one of the concerns raised by the accreditation report in 1959.

Modernization

Enrichment Program. Although the Academy’s initial curriculum was modeled after that of West Point, the faculty was quick to recognize the need to allow cadets to enrich and accelerate their education. The West Point faculty had provided a formal Advanced Academic Program for qualified cadets for several years, but their curriculum was still fully prescribed with no other enrichment opportunities. Colonel Higdon had successfully experimented with advanced mathematics courses during the first semester in Fall 1954. This led to advanced courses in mathematics, chemistry, English, and graphics in the fall of 1956 and the Enrichment Program proposed by Colonel McDermott and approved in the spring of 1957. The Enrichment Program provided four basic ways to enrich the cadets’ academic program: (1) transfer credit, (2) validation credit, (3) substitution of an advanced course for a prescribed course, and (4) overload, by voluntarily taking one or more courses beyond the normal semester requirement.

Many consider this USAFA Enrichment Program the trigger for the most significant academic achievement in the history of the Academy. Its significance can be understood because it led to the introduction of academic majors, and increased graduate school opportunities, as well as to adoption of majors at the other military academies.

Optional Majors. All cadets were expected to carry equal six-course loads each semester, so cadets with validation or transfer credits could concentrate on a discipline by filling vacancies with selected courses and/or overloading. Thus, the Enrichment Program led in 1958 to the approval of three defined majors. Other majors could be constructed by a cadet working with a Department Head who then obtained approval by the Faculty Council and the Dean. Other majors were added and approved. When the first class graduated in 1959, over 11 percent of the class had earned a major in Basic Science, Engineering Sciences, English, or Public Affairs. The success of these programs prompted General McDermott in October 1959 to propose that the Academy provide graduate training and grant Master’s degrees. Although the proposal was supported by the faculty, the Academy Board, the Superintendent, and the Air Staff, it ultimately failed because it was strongly opposed by the other academies and the Air Force Institute of Technology. For the Class of 1960, majors in Aeronautical Engineering and Humanities were added, and nearly 30 percent of the class earned a major. By the time the Class of 1965 graduated, the Academy had made available additional majors in History, Management, and Astronautical Engineering (the latter was the first undergraduate degree in that discipline in the country). It is a testament to cadet academic ambition that nearly 86 percent of the Class of 1965 took 18 to 22 semester hours beyond the core to earn a major, and more than 8 percent of the class had earned two majors.

Majors for All. The next innovation, in 1964, was the “majors for all” program wherein all cadets beginning with the Class of 1966 would earn an academic major. Additional core options had been added increasing the total to four, to be chosen from a limited list. Graduates in 1966 earned degrees in nine academic disciplines, and nearly12 percent of the graduates earned two majors. However, it soon became clear that it was unrealistic for every cadet to complete all requirements for a disciplinary major within the allotted four years. In order to allow otherwise worthy cadets to graduate, the Academy Board created divisional majors for the Class of 1967 and subsequent. This provided a path to graduation for a cadet who failed a required course in a disciplinary major but still had sufficient credits to graduate. Further flexibility was provided in 1975 when, effective with the Class of 1979, the Academy Board was able to graduate a cadet without an academic major under unusual circumstances. The “majors for all” requirement was discontinued in 1981, when the Basic Academic Program was introduced and majors became optional. However, almost all cadets graduate with a disciplinary major. In the Class of 2014 only 3 out of 1,073 had no major while 25 had double majors. More than 30 majors are now offered, including six interdisciplinary majors. The table in Appendix E identifies majors by the year they were introduced. The current majors are listed with their sponsoring department(s) in Chapter 4.

Maintaining a Balance

Major curriculum changes normally occurred because of significant program reviews, which are described briefly below. A table with additional details is in Appendix E. From the very beginning, the Air Force Academy has welcomed the advice of civilian educators as consultants. These include committees or boards convened by Congress, the Department of Defense, or the Air Force; the Academy’s Board of Visitors; and the numerous accreditation evaluations. All have had a varying degree of influence on the curriculum. Virtually all external input has strongly supported the basic principle of a core curriculum balanced between humanities and social sciences on the one hand and basic sciences and engineering on the other.

During 1969–1970, an ad hoc committee of the Curriculum Committee completed a comprehensive review of the core curriculum. One driver was the desire for all flight-qualified cadets to be able to complete the Pilot Indoctrination Program using the T-41 aircraft without having to overload. The Curriculum Committee recommended, and the Academy Board approved, a core course reduction from 38 to 36 courses (105 to 99 semester hours) effective with the Class of 1974. This also entailed changes to practically all majors’ programs, specifying fewer hard requirements and allowing more cadet choice of major course options.

In 1973–1975 the internal 20th Anniversary Study, under the leadership of Permanent Professor Phil Erdle, was a complete introspective examination of every program affecting the cadet way of life. The study’s Curriculum Review Committee was six Permanent Professors and two additional officers representing military training and physical education. The study reaffirmed the principle of the core, the balance within the core, and the majors’ programs. After considering nearly 200 proposals, the Curriculum Committee approved changes that became fully effective with the Class of 1980. At this time, to provide the cadets more flexibility and choice, four divisional majors (Humanities, Social Sciences, Engineering, Basic Science) were created. A new Aviation Science major was also introduced for classes from 1978 to 1985 with the same reduced major’s requirements as the divisional majors. To address cadet workload the academic graduation requirement was reduced from 145½ semester hours (53 courses) to 138 or 144 semester hours (46 to 48 courses), depending upon the major chosen. This reduction was obtained by reducing majors’ requirements to 27 semester hours for the divisional majors or 33 for the interdisciplinary and disciplinary majors. However, based on AF requirements five courses were added to the core: Modern Physics, Material Engineering, Engineering Design, English, and Management, which increased the core from 99 to 111 semester hours. An additional change in the attempt to increase science and engineering graduates was to move core engineering courses so cadets encountered them in earlier semesters. Changes also included adoption of equal-length semesters beginning in Fall 1976 (previously 15 weeks fall and 18 weeks spring), reduction of the daily schedule from seven 50-minute periods to six 60-minute periods, and establishment of a flight core requirement for all cadets (T-41 or Aviation Fundamentals for non-rated). To facilitate the latter and allow more time for cadets in high leadership positions, cadets became eligible to take a course in the summer prior to their final year to reduce their course load. The implementation of equal 42-lesson semesters had far-reaching consequences as it increased scheduling flexibility and reduced course preparation and printing costs. Fall semester examinations prior to the Christmas break were retained.

The next significant internal review was the 25th Anniversary Review Committee in 1979. Using results of this study, the “majors for all” requirement was relaxed and cadets were then able to choose, or be directed to, the Basic Academic Program, or BAP. The BAP had the fewest number of courses and semester hours required for graduation. Its purpose was to “provide another form of academic self-determination for cadets.” Among other things it allowed for special concentrations to make an individual more competitive for medical school or a specific graduate scholarship opportunity. It also offered a graduation alternative for cadets unable to complete a major in four years.

In 1985–1986 a major curriculum review that focused on the relevancy of each core course produced changes that provided greater flexibility for the cadets and departments to structure their majors. A reduction in the core from 37 to 30 courses (111 to 90 semester hours) was conditioned on the departments providing more elective courses within their majors’ requirements and giving every cadet at least one completely unspecified optional course. Thus, elective courses increased to 15 (45 semester hours) in the divisional majors and 16–18 (48–54 semester hours) in the disciplinary majors. In some cases, the former core courses had to be added to the major’s course requirements. For example, two mathematics courses deleted from the core were still required in several engineering, interdisciplinary, and basic sciences majors. The principle of a “tracked core” was also introduced, which provided different versions of core courses depending on the cadet’s major. These were generally tailored with one version for humanities and social sciences majors and the other for basic sciences and engineering, although which version was required for a major was left to the departments (with Curriculum Committee approval.)

The decade 1990–2000 saw no major reviews of the curriculum other than those by accrediting organizations. However, there was a series of changes to the core. In 1991 a graduation requirement for a grade point average of at least a 2.00 (C) in the core courses was established to ensure basic competency in the core subject matter. Also notable was increased emphasis on foreign languages. In 1994 the introductory courses increased from 4½ to 6 semester hours with contact time increased to daily meetings. In 1997 the requirement for two semesters of language regardless of major was restored for all cadets unless they passed a proficiency test.

The Dean, Brigadier General Randy Cubero, started identification of learning outcomes at the Academy in the mid-1990s. Measuring achievement of self-identified outcomes became the method used by the accrediting agencies ABET and HLC/NCA during the 2000s. The Academy developed outcomes for all facets of the cadet experience. Now each course or activity was expected to state their learning goals and objectives in terms of outcomes. In turn, core courses were required to show how their outcomes contributed to the Academy outcomes that defined what all cadets should have learned by graduation. This activity was led Academy-wide by Permanent Professor Tom Yoder. Of course, within each department a review of every course was led by the Permanent Professor/Department Head, assisted by the department’s curriculum committee and each course director. These outcome-based analyses drove curriculum changes beginning in the mid-2000s.

A major curriculum change was accomplished during 2002–2004 for the Classes of 2006 and subsequent. The Air Force stated a need for more basic science and engineering graduates, and it was hoped that a “leveling of the playing field” would encourage more cadets to enroll in majors in those fields. Total semester hour requirements were reduced to 141 for divisional majors and 147 for disciplinary and interdisciplinary majors. This change maintained a reasonably balanced core curriculum, while reducing the total core requirements, and provided more choice and flexibility in the majors’ programs. Previously constrained majors created more options, and all disciplinary and interdisciplinary majors now required the same number of courses. The change added a core leadership course but still reduced the core academic curriculum from 94 to 91 semester hours and accommodated the new Academy Flight Screening Program. The new core curriculum required 48 semester hours in basic sciences/engineering and 43 semester hours in humanities/social sciences. To recognize the global Air Force mission, the foreign language exposure increased for many cadets by requiring four semesters of language for all humanities and social science majors regardless of skill level. With the increased emphasis on outcomes, the goal of producing leaders of character was affirmed by requiring successful participation in each of the character development programs that were tailored by the Commandant for each class.

The Basic Academic Program was discontinued with the Class of 2000 and “majors for all” returned. However, it soon became evident that an alternative to the BAP was needed, and the Bachelor of Science Program (BSP) was adopted. The BSP is an alternate path to graduation below the divisional majors’ requirements with 132 semester hours required. The BSP has entry restrictions and results in a Bachelor of Science degree with no major, again ending the “majors for all” requirement with the Class of 2007.

During 2006–2008 a “transformed” curriculum was approved and implemented for the Class of 2011 and subsequent. Two years of curriculum transformation efforts at the Academy developed the following significant changes: added Portuguese as the eighth foreign language taught at the Academy, added a 1-semester-hour First Year Experience course designed to develop cadet skills and knowledge to successfully and responsibly engage in the learning process, and replaced two engineering core courses with a Science and Technology Energy/Systems Core Option and the other with a first-year course, Introduction to Air Force Engineering, to better attract engineering majors through an experience earlier in the curriculum. As part of this transformation, the Academy Board also approved the institutional USAFA Outcomes content, which included all seven Educational Outcomes, and the outcomes development and assessment processes. These processes included breaking down the high-level outcomes into four supporting tiers of ever-increasing specificity and detail. In turn, this created many minor curriculum changes as lower level USAFA Outcomes were incorporated into core course descriptions in the Curriculum Handbook. The outcomes process has led to increasing integration among the core courses and greater assurance that each course builds on previous courses and cadets can be held accountable for their prior learning experiences.

During the Academic Year 2008–2009 the Academy revised the USAFA Outcomes content, revised the outcomes development and assessment processes, and established the unmanned aerial systems (UAS) course sequence composed of a summer airmanship course and two UAS upgrade courses. The next academic year divisional core equivalent courses were established to provide flexibility in awarding credit for coursework completed by USAFA cadets during Study Abroad, International Exchange, and Service Academy Exchange programs. In 2011 a new major in Philosophy was established, and the next year saw a new major in Applied Mathematics. Also in 2012 a major change was developed by the Division Chairs to closely align the core courses with the Academy Outcomes. The Curriculum Committee concluded more work was needed and the proposal was not supported. This alignment would become a major feature of the next major revision. The requirement for all cadets to complete two semesters of foreign languages was reinstated in 2015, and the four divisional majors were replaced by a General Studies major in which a cadet chooses a coherent course of study in engineering, basic sciences, humanities, or social sciences.

External forces drove the next major curriculum change. The Congress imposed budget sequestration constraints that led to elimination of 35 faculty manpower positions. In turn, the core curriculum was reduced by three courses. While realigning the core curriculum with the Academy Outcomes, some courses were increased in credit from 3.0 semester hours to 3.5, 4.0, or 4.5 semester hours. The net change was from 32 academic courses (96 semester hours) to 29 courses (93 semester hours).. The changes approved in 2017 became fully effective with the Class of 2021. Adjustments were needed for the Classes of 2019 and 2020 during the transition to the new curriculum. Much effort was expended to ensure that each course in the new core curriculum supports the nine Academy Outcomes:

— Critical Thinking

— Application of Engineering Methods

— Scientific Reasoning and the Principles of Science

— The Human Condition, Culture, and Societies

— Leadership, Teamwork, and Organizational Management

— Clear Communication

— Ethics and Respect for Human Dignity

— National Security of the American Republic

— Warrior Ethos as Airmen and Citizens

The core curriculum consists of 29 Dean of Faculty academic courses (93 semester hours), 10 Athletic Department physical education courses (5 semester hours), one course each year administered by the Center for Character and Leadership Development, a significant number of Commandant of Cadets military training and leadership courses and programs, and airmanship courses that require satisfactory completion.

The new core consists of courses at the foundational, intermediate, and advanced levels, all carefully designed to support one or more of the above outcomes while providing a closely knit, coherent core course of study. It includes carefully constructed options for cadets to select courses at the two upper levels. Foundational courses are prescribed. At the intermediate level the cadet must choose one of three mathematics courses or a behavioral sciences two-course sequence to learn statistical reasoning in support of the “Critical Thinking Outcome.” The second intermediate level option is a choice of two out of three basic science courses that support the outcome “Scientific Reasoning and the Principles of Science.” The advanced level options are three choices within two “baskets” of upper division offerings. Each course among these choices is aligned with educational outcomes as described below. Basket Choice #1 is the Advanced Science, Technology, Engineering, and Math (STEM) Option, where cadets pick one course from a list of courses that support “Application of Engineering Methods” or “Scientific Reasoning and the Principles of Science.” Basket Choice #2 is the Advanced Sociocultural Option, where cadets pick one course from a list of courses that support “The Human Condition, Cultures, and Societies,” “Leadership, Teamwork, and Organizational Management,” “Ethics and Respect for Human Dignity,” “National Security of the American Republic,” or “Warrior Ethos as Airmen and Citizens.” Choice #3 is the Advanced Open Option where cadets choose any course from either Basket #1 or #2. In terms of relative balance, the new core curriculum requires 13 basic sciences and engineering courses (43 semester hours) and 14 humanities and social sciences courses (44 semester hours), including Basket Choices #1 and #2.

Enhancing Cadet Performance

The principal enhancements in the curriculum relating directly to the core and majors were described above. The present section describes some curriculum enhancements of a more general nature as well as many other opportunities created by the Permanent Professors for cadets to excel.

Enhancements within the Curriculum

Independent Study Courses. Every cadet with a schedule that allows an open elective course and adequate academic standing may pursue independent study of a subject approved by a faculty mentor and the Department Head. The independent study elective for credit became available through a curriculum change effective for the Class of 1966. These studies can be set up for one, two, or three semester-hours of credit. The courses range from individual study and tutorial on a specific topic, to intensive reading and analysis, to creative writing, or even to independent laboratory research. Each independent study normally culminates in a written report. Over the past several academic years, independent study courses averaged about 425 enrollments per year, usually for three hours credit, and mostly by senior cadets in the spring semester. This is in addition to the capstone courses described below.

Capstone Courses. Engineering (Engr) 400 was introduced in 1976 as a design course required for all cadets. Design challenges were presented to the cadet section, who worked as a team to thoroughly research the design problem, possible solutions, and methods for implementing their chosen solution. Engr 400 was often cited by graduates after several years of service as one of the most, if not the most valuable course they had taken. Regardless, pressure to achieve other learning outcomes led to the demise of Engr 400 (later Engr 410) as a core requirement in 2005. However, since then capstone courses have been added to many majors to provide cadets the opportunity to integrate and apply their knowledge by solving realistic problems. Capstone design courses have been an integral part of each engineering major, as well as majors such as Behavioral Sciences and Operations Research, because of the widely recognized need by industry and the armed services for such experience. Indeed, most Academy majors now have a capstone course requirement, known variously as Capstone Design, Capstone Seminar, Capstone Research, Capstone Practicum, or even Capstone Thesis. Following the process used by their discipline, cadets as individuals or often in teams perform research to fulfill the requirement presented to them. An individual or team of faculty will mentor the cadets as they progress through the one- or two-semester course. Most teams are now interdisciplinary, so valuable lessons on leadership, followership, and team dynamics are also learned.

Auditing. Another way for cadets to enrich themselves is by auditing courses. Upper-class cadets may audit a non-core course with permission of the appropriate Department Head. Obviously, the cadet may not later take for credit any course they audited (or even began to audit). The expectation is that the auditor will do some preparation for the course but will not participate in graded assignments or take examinations.

Space, UAV, and RPA Operations. With the sophistication of Academy research in space, unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs), and remotely piloted aircraft (RPA) cadets are afforded many opportunities to develop valuable operational skills. A Basic Space Operations course allows cadets to staff the Academy ground station, leading to certification as space operators for the FalconSat program and awarding of basic space operations wings. Cadets in other courses can do ground school and pilot training with small UAVs and RPAs, leading to Flight Test Operator status. Over 300 cadets per year are participating in these programs.

Academic Honors Program. A new academic Honors Program was added to the Academy’s curriculum in Fall 1980. It was not an honors major but instead offered the participating cadets special honors versions of existing core courses. The program was voluntary and offered the benefit of having an enhanced classroom environment and the opportunity to graduate “with Honors.” The Honors Program was discontinued with the Class of 1993, but some departments continued offering honors sections of core courses for another decade. The opportunity of gathering the best students into special sections of courses resurfaced with the Academy Scholars Program.

Academy Scholars Program. Beginning with the Class of 2007, each cadet who completes the requirements of the Academy Scholars Program graduates as an Academy Scholar. The Scholars Program was instituted by the Dean, Brigadier General Born, to better develop a pool of intellectually inspired and well-rounded scholarship candidates who would be comfortable in scholarship competitions. The program aims to help selected volunteer cadets reach their full potential by offering a challenging path through the core curriculum starting in their second semester. The Scholars curriculum initially consists of special core course sections (core substitutes) that deepen the scholars’ intellectual development, primarily in the liberal arts. Cadets who wish to take Academy Scholars courses, but who are not formally in the program, may do so on a space-available basis with the approval of the program director. The pedagogical principle of this enrichment program involves forming small learning communities (a cohort of cadets enrolled in the same sections) to provide close interaction among the same students over a four-year period, in courses pursuing a coherent theme—the development of the Western intellectual tradition. The Permanent Professors play a key role by early identification of cadets for the program. At present about 50 cadets per year graduate with the Academy Scholar distinction. Most of the cadets who win nationally competitive scholarships come from the Scholars group.

Foreign Exchange Programs. A significant element of enhancing cadet experiences is the Foreign Exchange Program, which has enabled thousands of cadets to travel and study abroad and to interact with foreign cadets at the Air Force Academy. It all started with the cadet exchange program with l’École de l’Air, the French Air Force Academy, initiated by Permanent Professor Al Miele as a way to strengthen the bonds of friendship and understanding between the two Air Forces at a time when France was distancing itself from NATO. In 1969 nine USAFA cadets from the Class of 1970 were sent to Salon-de-Provence for the fall semester and six French cadets came to USAFA. This successful exchange has continued for nearly 50 years, with up to eight cadets exchanged each way, each year.

That insightful beginning demonstrated the benefits of offering cadets opportunities to study a foreign language in a foreign culture, and its success encouraged other efforts. The Academy has now substantially expanded exchange opportunities and includes opportunities for a semester of study at foreign universities as well as military academies. For the semester abroad programs, each candidate must demonstrate how the specific courses in the semester abroad fit into the requirements of their academic major. For the Academic Year 2017–2018, 36 Academy cadets went for a semester to foreign academies in Brazil, Canada, Chile, Colombia, France, Germany, Japan, Singapore, and Spain; and USAFA welcomed a similar number of semester exchange cadets from these countries. Another 22 cadets studied for a semester at civilian universities in Brazil, China, Georgia, Japan, Mexico, and Morocco.

Ensuring Up-to-Date Technology

When the academic building, Fairchild Hall, was constructed at the permanent site, it was equipped with a closed-circuit television system that distributed to each classroom and lecture hall. This provided the faculty a unique capability that they exploited to enhance cadet learning.

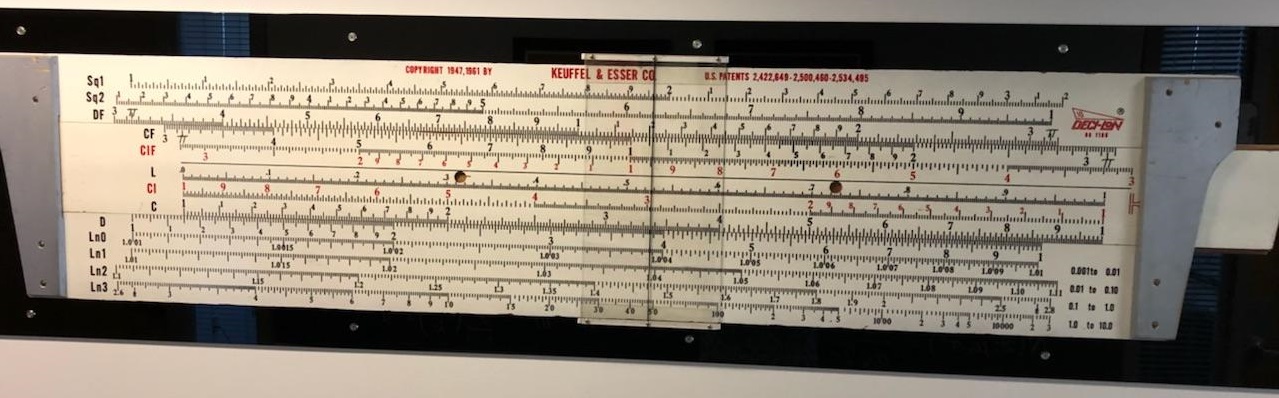

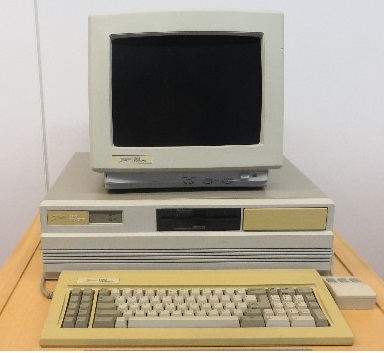

The first classes of cadets were issued slide rules to assist them in making calculations in technical courses. The Department of Mathematics was responsible for teaching cadets how to use the slide rules and had large, 6-foot-long demonstration models in the classrooms as seen in the photo. When the Frank J. Seiler Research Laboratory was established at the Academy in 1962, it installed a mainframe computer partly justified to support the Academy. Soon, terminals were being used to teach computer programming, to access the library’s card catalog, for research, and for other academic and administrative tasks. By 1988 the Directorate of Academic Computing Services under the Dean of the Faculty operated 14 minicomputers, which had replaced the large mainframe, as well as several microcomputer and terminal laboratories. In addition, there were several analog computers for certain calculations in engineering and physics.

The first classes of cadets were issued slide rules to assist them in making calculations in technical courses. The Department of Mathematics was responsible for teaching cadets how to use the slide rules and had large, 6-foot-long demonstration models in the classrooms as seen in the photo. When the Frank J. Seiler Research Laboratory was established at the Academy in 1962, it installed a mainframe computer partly justified to support the Academy. Soon, terminals were being used to teach computer programming, to access the library’s card catalog, for research, and for other academic and administrative tasks. By 1988 the Directorate of Academic Computing Services under the Dean of the Faculty operated 14 minicomputers, which had replaced the large mainframe, as well as several microcomputer and terminal laboratories. In addition, there were several analog computers for certain calculations in engineering and physics.