The Genesis of the United States Air Force Academy

Not long after the first manned heavier-than-air aircraft flight, informed by the experience of World War I, early airmen recognized the unique training required for an air service comparable to the United States naval and ground forces. Since the air service was a part of the US Army, it was natural for the United States Military Academy at West Point, New York, to serve as a model. This chapter briefly traces the actions leading to the establishment of the United States Air Force Academy, the factors that so strongly influenced its founding principles, and the leadership that guided its early days.

Quick Outline

The Long Road to Today’s Academy

Meeting the Start-Up Challenges

USMA Tradition: Shaping the United States Air Force Academy

Early Leadership Sets the Tone

The Long Road to Today’s Academy

With the first flight by the Wright brothers at Kitty Hawk, North Carolina, on December 17, 1903, it could be argued it was inevitable that there would someday be an Air Force Academy. However, the road to the opening of such an academy was long and arduous, contrasted with the rapid acceptance of the airplane as an instrument of war. Under the supervision of the Army’s Signal Corps Aeronautical Division established in 1907, the Army accepted its first aircraft, the Wright brothers’ “Flyer,” on April 2, 1909, after fewer than eight months of testing. Only two years later came the first wartime use of aircraft for reconnaissance, artillery coordination, and bombing by Italy and Bulgaria, 1911–1913. Congress authorized an Aeronautical Section of the Signal Corps in 1914. The US Navy had commenced pilot training two years earlier. The first American use of heavier-than-air aircraft in military operations came on March 13, 1916, when the Signal Corps’ 1st Aeronautical Squadron performed aerial reconnaissance along the US border with Mexico. Shortly thereafter 38 American pilots prepared for combat in World War I as volunteer members of the French Foreign Legion’s Lafayette Escadrille Squadron formed by the French government in April 1916. (To join this squadron required a pledge of allegiance to the French Foreign Legion, not to a government, so it avoided the loss of citizenship that had deterred American volunteers from joining other nations’ air forces already in the fight.) The squadron fought in the Battle of Verdun and the Somme Offensive during 1916, becoming known for daring and effectiveness. The United States entered World War I on April 6, 1917, but had no modern combat aircraft and only fledging training programs. Their first combat was not until October 1917. Although the Air Service did participate in the Second Battle of the Marne at Château-Thierry and Belleau Wood in early 1918, their first offensive action was not until the Battle of Saint-Mihiel in September 1918. Many of the American members of the Lafayette Squadron were absorbed into American units, providing valuable combat experience. At the beginning of the war, the Signal Corps’ air arm numbered 1,200 personnel. When the armistice was signed on November 11, 1918, the US Army Air Service was 195,000 strong with 78,000 personnel in Europe. More than 10,000 pilots manned 42 air squadrons.

Just 15 days later, on November 26, 1918, there was the first formal call for a separate air academy. Lieutenant Colonel Hanlon, Chief of the Mechanical Instruction Branch, wrote in a letter to the Air Service Chief of Training: “As the Military and Naval Academies are the backbone of the Army and Navy, so must the Aeronautical Academy be the backbone of the Air Service.” His letter went on to state goals and objectives for such an academy, urge Congressional action, and recommend the appointment of a board of officers to undertake site selection and detailed planning for establishing and operating a United States Aeronautical Academy. Within a month the President of the University of Texas made the first of what would become many offers of a site location, when he offered a site near Austin for an Air Service Academy, provided it had the same relationship to the Air Service as West Point did to the Army. The November 26, 1919, Comments on Strength, Organization, and Training of the Air Service, Pamphlet No. 12, published by the Office of the Director of the Air Service, stated the policy that the only way to train Air Service officers was in the Air Service itself and this could best be done with an Air Service Academy. During 1919, aircraft industry members and Air Service officers including Brigadier General William “Billy” Mitchell had proposed, as had a resolution introduced into the House of Representatives, the creation of an aeronautical academy. The bill died at the end of the session. This flurry of activity introduced the issues that would plague proposals for an air academy for the next 34 years: what should be the mission, goals, and objectives; should the curriculum emphasize overall academics or technical and scientific subjects only; what military studies should be included and should flying training be required for all; what would it cost; and finally, where would it be located? Air Service leaders attempted to have Military Aviation introduced into the West Point curriculum in 1919, but they were rebuked by the Superintendent because there was no time available in the curriculum. Brigadier General Douglas MacArthur, who then became Superintendent, continued to ignore proposals by Air Service officers.

In 1922 a Senate resolution called for the Secretary of War and the Secretary of the Navy to report to Congress if it was feasible and advisable to establish a school for aeronautics and if it was practical for such a school to exist at the Naval Academy and the Military Academy. The resolution contemplated appointments to these academies of young men who desired to be commissioned in the US Army Air Service. The official response by the Secretary of War came less than a month later. It stated that while it was feasible, it was neither practical nor advisable because the country’s need for aviators was being met by existing training. Meanwhile perhaps the most vociferous of the advocates for military aviation was Brigadier General Billy Mitchell, Assistant Chief of the Air Service. His speeches and writings were supported by pilots of the Air Service, whose flights were setting new records in 1923–1924, demonstrating to the public the promise of military aviation. General Mitchell’s outspoken efforts resulted in the loss of his job and return to his permanent rank of colonel. His inflammatory rhetoric following the Navy’s Shenandoah dirigible disaster in 1925 and multiple airplane crashes led to his court-martial and resignation. This controversy diminished the calls for an air academy, but not the need for Air Service training.

By 1925 the Air Service had established training centers for officers and airmen at Brooks and Kelly Fields in Texas, at Scott and Chanute Fields in Illinois, McCook Field in Ohio, and an Air Tactical School at Langley Field in Virginia. In 1930 Randolph Field, Texas, was dedicated and soon became the center of Air Service training. In 1934 the Baker Board, chaired by former Secretary of War, Newton D. Baker, recommended that West Point provide cadets with 20 hours of flying training. Reluctantly, West Point officials finally implemented 25 hours (14½ in the air) of training in the summer of 1936. These training centers; the doctrine developed at Langley and later at Maxwell Field, Alabama; and the West Point training comprised the resources available to the United States when it entered World War II in December 1941. Congressional action early in 1942 allowed the West Point training to expand so that by the summer of 1942 60 percent of the senior and junior classes had volunteered and were receiving flying training. By the end of September 1945, following the surrender of Germany and Japan that ended World War II, 657 West Point cadets had received flying training. To put this in perspective, between July 1939 and August 1945, the US Army Air Corps advanced flying training schools had commissioned 190,443 pilots. World War II had clearly demonstrated the critical importance of air power in the defense of the United States and the need for a substantial number of dedicated, well-trained officers to carry out this mission.

To further the concept of a separate Air Academy, Army Regulation 95-5 created the United States Army Air Forces (AAF) on June 20, 1941. Major General Henry H. “Hap” Arnold became Chief of the Army Air Forces and Acting Deputy Chief of Staff for Air with authority over both the Air Corps and Air Force Combat Command. By agreement between the Army Chief of Staff, General George C. Marshall, and Arnold, debate on separation of the Air Force into a service co-equal with the Army and Navy was postponed until after the war. In 1942, acting on an executive order from President Roosevelt, the War Department granted the AAF full autonomy, equal to and entirely separate from the Army Ground Forces and Services of Supply. The Air Force Combat Command and the Office of the Chief of Air Corps were abolished, and Arnold became AAF Commanding General and an ex officio member of the Joint Chiefs of Staff. Further enhancing the AAF’s status, in March 1943 Arnold was promoted (wartime) to full general, and in December 1944 he was appointed a five-star General of the Army, placing him fourth in Army rank seniority behind Marshall, MacArthur, and Eisenhower. In October 1944, anticipating the war’s end, Lieutenant General Ira C. Eaker (co-author with Arnold of three books extolling the merits of air power [1936, 1941, 1942]) wrote Arnold urging him to propose legislation to establish an air academy.

Even before the end of World War II hostilities with Japan in August 1945, members of Congress began submitting proposals for an air academy. Some included specific locations, ranging from Texas to Colorado and Missouri to California, or leaving selection of the location to military leaders. None of the nine resolutions proposed between 1945 and 1950 made it out of committee as they were not supported by the War Department or, later, the Department of Defense. Indeed, it was the National Security Act of 1947 establishing the Department of Defense and a separate United States Air Force that started serious efforts by the Air Force to solve the problem of maintaining a well-trained officer corps. After much negotiation, the first Secretary of the Air Force, Stuart Symington, worked out an agreement with the Army and the Navy that 25 percent of the graduates from their academies could volunteer to be commissioned in the Air Force beginning with the Class of 1949. A condition was that at least half of the volunteers had to be medically qualified to be pilots. In exchange, the Air Force was to provide qualified officers to teach subjects in the curricula of Annapolis and West Point. This last point later proved to be valuable in establishing the Air Force Academy academic program because it forced the Air Force personnel system to identify officers with advanced degrees in the subjects taught at the academies. It also caused the establishment of a system for officer advanced academic education to provide an ongoing supply of qualified instructors. The activation of numerous reserve officers for the Korean War in the early 1950s provided a second opportunity to identify officers with wartime experience and advanced degrees. Many of these officers so identified had been teaching at civilian institutions.

Meanwhile Secretary Symington, senior Air Force leaders, and the Secretary of Defense initiated studies and convened several boards to study air academy options as well as the broader issue of the role of service academies in the defense of the nation. The most extensive of these efforts was the full-time Air Force Academy Planning Board, which had been established at Air University, Maxwell AFB, AL, after the Air Force Chief of Staff, General Hoyt S. Vandenberg, designated Air University as the agency responsible for air academy planning. This Board published its report in January 1949. The report reiterated many of the reasons for an air academy put forth in Air Service memoranda in 1919 and 1922. It was very detailed as to site selection criteria, goals, objectives, and curriculum content and was remarkable for its close resemblance to the other service academies, especially West Point. This multitude of studies and reports prompted Secretary of Defense James Forrestal to appoint a Service Academy Board in March 1949. This prestigious Board was co-chaired by retired General Dwight D. Eisenhower, President of Columbia University, and Dr. Robert E. Sterns, President of the University of Colorado. This Board was charged to look at all aspects of the service academies as well as reserve officer training at civilian institutions and make any necessary recommendations for improvement. Its final report in January 1950 strongly supported the service academies and the establishment of an Air Force academy equal in stature to the Army and Naval academies. Further, it emphasized the attributes that the academies should develop in their cadets including educational knowledge, practical experience, mental alertness, problem-solving abilities, motivation, morality, and a commitment to high morale and spirit as well as service to the nation. Now the task became to obtain legislative approval for the air academy.

In 1949 proposed legislation for an air academy was introduced in the House of Representatives, and a request was submitted by the Secretary of Defense. Opposition by the Bureau of the Budget effectively killed both initiatives. Next, a bill was produced by the Air Staff to meet Bureau of Budget objections and introduced by the Chairman of the House Armed Services Committee, Carl Vinson, in August 1949. However, the Air Staff immediately began working on an improved bill, and Chairman Vinson directed his staff to write a new bill to correct objections he had to the existing one. Soon Vinson announced that the site location should be included in the bill. In December 1949, General Vandenberg decided a dedicated staff at Headquarters USAF was required to handle matters pertaining to the air academy. Lieutenant General Hubert R. Harmon was put in charge. In mid-1951 a proposal fully coordinated within the Department of Defense and by the Bureau of the Budget was introduced by Chairman Vinson, but no hearings were conducted on the bill in 1951 or 1952. The elections of 1952 caused further delay as the Republican Party took control of the Congress and the White House. General Harmon and his staff worked diligently to inform the new executives and members of Congress of the need for an air academy. Finally, in January 1953, a bill fully coordinated within the Executive Branch and nearly identical to the previous one was introduced; however, hearings were postponed until a year later. Committee hearings were conducted by the House Armed Services Committee in January 1954 and the Senate Armed Forces Committee in February. The House approved the measure on January 21 and the Senate on March 8. A conference committee agreed on a compromise bill on March 29, and both chambers approved the bill later that day. On April 1, 1954, President Eisenhower signed Public Law 325, ending the 35-year quest for an Air Force Academy. The next challenge was to complete the search for a site for the Academy.

Meeting the Start-Up Challenges

In late 1949 as legislative activity increased, Secretary Symington appointed an Air Force Academy Site Selection Board. This Board studied 354 sites in 22 states recommended by individuals, chambers of commerce, or governmental agencies. Using many of the criteria developed earlier by the Air Force Academy Planning Board, the sites under consideration were narrowed down to 29. These 29 were personally visited by the Board members, who then produced a list of eight sites: Camp Beale, CA; Colorado Springs, CO; Grapevine, Randolph AFB, and Grayson County, TX; Charlotte and Salisbury, NC; and Madison, WI. The Board declined to make a selection but wrote a memorandum expressing their preference for the Colorado Springs site. This memo was placed in a sealed file in the Secretary of the Air Force’s office by General Harmon, and the Board was dissolved in late 1952. The 1954 act that President Eisenhower signed into law authorized the Secretary of the Air Force to select the academy site upon the unanimous recommendation of a five-member site selection commission established by him. There were provisions for reaching a decision if a unanimous recommendation was not obtained.

Secretary Talbot appointed a Site Selection Commission composed of former Air Force Chief of Staff General Spaatz; Lieutenant General Harmon; Dr. Virgil Hancher, President of Iowa State University; Merrill C. Meigs, Vice President of the Hearst Corporation; and Reserve Brigadier General Charles Lindberg. Secretary Talbot met with them one day before the announcement of their appointment on April 6, 1954. The announcement was accompanied by a solicitation for nominations of potential sites. By the cutoff date of April 21, proposals had been received from 580 sites in 45 states, including 57 in California and 51 in Texas. The commission developed site criteria that were added to and refined as their work progressed. Chief among the additions was one recommended when the Board visited West Point and Annapolis to gather their views on requirements for a suitable site. Both academies felt their effectiveness was hampered by a lack of space to expand. Therefore, the commission decided the site should contain at least 15,000 acres of land. The commission considered each site, taking advantage of the previous Site Selection Board’s data and findings when appropriate. The commission visited 34 sites and viewed an additional 33 from the air. When the site visits concluded, the commission met in the Pentagon, and General Harmon read the previously sealed recommendation letter from the Site Selection Board. Three of the commissioners wanted Colorado Springs, but the two civilians were opposed or undecided. So General Lindbergh agreed to accompany these two to Colorado Springs, which also would allow him to confirm that the altitude would not hinder cadet flying training. (It was during this visit that the Pine Valley Airport manager, much to his embarrassment, failed to recognize General Lindbergh when he tried to rent a plane.) After many phone calls and a final meeting in the Pentagon among the Air Force Chief of Staff, General Nathan F. Twining; General Spaatz; Mr. Meigs; and General Harmon, the commission decided to recommend three sites to Secretary Talbot. The sites recommended in their final report on June 3, 1954, were the site about eight miles north of Colorado Springs, one roughly 10 miles from Alton, IL, and one on the south shore of Lake Geneva, WI.

The announcement of the three sites caused a varied reaction among the residents of the three areas. In Illinois and Wisconsin, more densely populated areas than the Colorado Springs venue, there were mixed reactions that included organized public protests. The few objections in Colorado Springs were overwhelmed by a very favorable response by a group organized by the Chamber of Commerce. This group had been working together diligently since 1949 to bring the Academy to Colorado Springs. The Governor of Colorado and the state legislature encouraged the selection of Colorado Springs, with the latter appropriating $1 million to purchase the required land. Remaining health concerns and water supply questions were dispelled by favorable results from medical studies and arrangements by Colorado Springs officials to purchase water and have it piped across the mountains to a treatment plant to be built on the south side of the proposed Academy site. Secretary Talbot announced his selection of the site north of Colorado Springs on June 24, 1954. At the same time, he announced a temporary site would be established in Denver while construction took place at the permanent site. The law establishing the Air Force Academy had authorized the expenditure of $1 million to provide a temporary site. General Harmon soon visited Denver and inspected the Army’s deactivated Fort Logan and Lowry AFB. On July 19 he recommended Lowry AFB to Secretary Talbot, who announced that day that Lowry was to be the interim site. These announcements must have been satisfying to President Eisenhower who enjoyed visiting his mother-in-law in Denver and vacationing in Colorado until his heart attack in 1955. His “summer White House” had been the headquarters building on Lowry AFB.

To direct all this effort as well as the manning of the new academy, Secretary Talbot wrote to General Harmon on July 27, 1954, that “The United States Air Force Academy is established and will operate as a separate operating agency… under the direct control of the Chief of Staff, United States Air Force….” He also said in the letter that the Academy would be attached to the Air Training Command for reporting, logistical support, and administration. On August 14, 1954, USAF Academy General Order Number 1 established the Academy at Lowry AFB effective July 27, and in the order General Harmon assumed command of the Academy effective August 14. His Pentagon office continued to provide support to the new academy, and its successor does so to this day. On that first day there were seven Academy personnel present for duty.

Lowry AFB was purchased by the Army in 1937 and a flying field was then built. Lowry provided technical training to more than 400,000 personnel during World War II but was being downsized following the armistice in Korea. Eventually the Academy rehabilitated 50 of the training center buildings. Some, such as the substantial brick buildings designed for training classrooms, transitioned quite easily into a U-shaped academic area. Twenty-four wooden two-story, open-bay barracks each were modified into 28 two-man dormitory rooms. The dining hall was named General Billy Mitchell Hall, and the social center for cadets was named General H.H. Arnold Hall. Both names would later adorn the buildings with the same functions at the permanent site. A cadet parade ground, six football fields, seven tennis courts, and five fields for softball were built.

With the work on facilities underway, the next priority was to bring to Lowry AFB the personnel who would welcome the first class that would report in less than one year. This work had been underway since 1948 when Air Force officers first began submitting applications for duty at an air force academy. The selection of the first members of the Academy faculty and staff was of utmost importance to the success of the Academy. Before examining this successful effort, it is useful to understand the foundational knowledge that had been gained from the operation of the United States Military Academy since its establishment in 1802.

USMA Tradition: Shaping the United States Air Force Academy

It is well known that non-British Europeans played a pivotal role in the United States winning the Revolutionary War. These Europeans, largely trained by war experience or in French and German military schools, directed the building of fortifications and the effective use of artillery fire. In the 1700s these schools had dropped their aristocratic traditions and had instead begun emphasizing mathematics, physics, chemistry, geography, tactics, and the use of artillery. After the war, American leaders agreed that the greatest danger to the new democracy was the rise of an aristocratic class that historically had been supported by armies in Europe. Reasoning therefore that armies were dangerous, our leaders conceived of an army led by officers trained at a military academy. Once trained, these officers would return to lead local citizen-soldier militias. This led to calls for establishing a military school to train engineers and artillerists for the defense of the new nation.

During the Revolutionary War, the largest fort in the American Colonies had been built at West Point to control river traffic at a narrow point in the Hudson River. A Polish military school dropout who then went to Paris to study drawing and military science before joining the American Revolution designed the fortifications at West Point. Congress authorized the purchase of the fortifications and surrounding land in 1790, increased the numbers of the Corps of Engineers and Artillerists stationed there, and established the rank of Cadet and the purchase of books in 1794. However, no books were bought and no classes held. In 1798 Congress authorized an increase in the Corps as well as the hiring of four teachers. But no qualified teachers could be found to fill the positions. Meanwhile in the 20 years following the end of the Revolutionary War, 19 colleges had been established in the United States, many of them by state legislatures who recognized they needed an educated populace to serve in local and state governments.

Finally, on March 16, 1802, Congress passed the Military Peace Establishment Act. Of the 29 sections in the act, 26 removed all military officer appointments, established a new method for appointing officers with detailed instructions on pay and rank, and authorized one regiment of artillerists and two regiments of infantry. Clearly, there was still a fear of a large standing army. The remaining three sections of the act authorized a Corps of Engineers to be stationed at West Point, which would constitute a military academy. The act authorized 7 officers and 10 cadets, while limiting the future total to 20 officers and cadets. The Chief Engineer was also to be the Superintendent of the academy. Classes began in April 1802 with the two authorized captains as instructors, one a graduate of Harvard, the other of Yale. Degrees were granted after one year of study by an Academic Board consisting of the Superintendent and the instructors. In spite of virtually no entrance requirements and what would now be considered little academic study, during the War of 1812, none of the fortifications built by West Pointers were lost to the enemy. Just prior to the war Congress had authorized an increase to 250 cadets, prescribed both age and mental prerequisites, and added three Permanent Professor positions in Natural and Experimental Philosophy (Physics), Mathematics, and Engineering. This set the general principles followed to this day. These Permanent Professors and the Superintendent made up the Academic Board. It is interesting to note that all cadets had to study the French language because the textbooks for their courses were all written in French. Still there was little discipline to the admissions, education and training, or graduation processes. It fell to the fifth Superintendent, Sylvanus Thayer, to create the system that would prevail until after the establishment of the United States Air Force Academy.

Before Major Thayer became Superintendent in 1817, he had graduated from Dartmouth College in 1807, but he did not attend the ceremonies because he was on his way to enroll in the Academy at West Point. He graduated in one year and became the Corps of Engineers’ Inspector of Fortifications in New England. He was an Assistance Professor of Mathematics at West Point in 1810. During the War of 1812, Thayer observed the poor performance of the American army and attributed it to lack of preparation. He requested a furlough to go to Europe and study the methods of education and training afforded officers there. Instead of being granted a furlough, however, Thayer was sent on official duty with funds to buy books, maps, and equipment for the Academy. He returned after nearly a year in France with about a thousand books as well as maps and charts that formed the basis of the first American military library. During his stay in France, Thayer became convinced that the French prescriptive method of education was the proper one. This method was used both in French military schools and the University of France and prescribed the entire course of study. It differed from the more liberal German elective method that Harvard faculty studying the German system at the same time decided to adopt. The latter system subsequently became the model for the rest of American higher education; but not West Point.

The Superintendent prior to Thayer had a very poor relationship with the faculty because, among other things, he imposed on their rights, refused to hold examinations, and granted commissions against their advice. Finally, he was removed by President Madison and Thayer was appointed Superintendent. Thayer first asked the faculty to provide him all the details of the courses they taught. In August 1817, after studying these submissions, Thayer began to lay out his proposed four-year course of study. Meanwhile he was imposing a discipline that had not been seen before. All cadets were on an indefinite vacation when he arrived; he called them all back. He then examined them and dismissed 43 for not meeting standards. He forbade cadets to bring money and ended the issuance of pay vouchers, so all cadets were on the same financial footing. Some graduates were not serving in the Army after graduation, so he made all cadets sign a pledge to serve at least one year. He canceled the annual vacations and instituted summer encampments where they learned soldiering in the field. Thereafter, the only time away from West Point that cadets would have was as Third Classmen (sophomores) when they would receive a summer furlough. He required all new cadets to report not later than June 25, in time for the encampment. He abolished favoritism and based advancement on merit alone. Cadet performance was evaluated through daily recitations, weekly ranking, and in semi-annual examinations. A system of demerits was implemented so that a cadet whose academic performance was excellent, but whose behavior was poor, would be properly evaluated. One of Thayer’s first acts had been to assign an army officer as Commandant of Cadets who was responsible for cadet tactical training, imposing discipline, and assigning demerits. A merit list was instituted so points awarded for good performance and deleted for bad behavior could be tallied in a non-personal, objective manner. A graduating cadet’s standing on this class ranking then was used objectively by the Academic Board to assign them to a corps in the army. A similar system is used to this day at all US military academies.

Thayer had found one additional aspect of both German and French education that he wanted to bring to West Point: the principal of forming small class sections containing students of like ability. To facilitate better cadet evaluation, Thayer added daily, graded recitations to the model. This method of instruction required more teachers, and Thayer was supported in his desire to have recent academy graduates assigned back to the academy to teach. Thayer’s goal was to free the Permanent Professors from teaching duties, so they could better guide execution of their programs. He also involved the Board of Visitors in the spring examinations. This Board, formed by the Secretary of War in 1816, was chartered to visit, evaluate, and provide reports to the Secretary. It was composed of outstanding men from every part of the country, including both critics and supporters of West Point. Thayer used this Board, continuous review of the curriculum and course content, and other means to significantly improve West Point’s reputation. This system of outside reviewers and attention to continuous improvement of academic instruction prevails at all the military academies today. This in turn made a West Point education desirable to young men and caused issues with admission to the academy, which Thayer struggled with. One result was a de facto rule of Congressional appointments, which exist to this day.

By the time Thayer left West Point in 1833, thoroughly discouraged by President Andrew Jackson’s nearly complete lack of support, all the serving Permanent Professors had been selected by him. This group was made up of 4 civilian Professors (Mathematics, Rhetoric and Moral and Political Science, Natural and Experimental Philosophy, and Engineering), 1 lieutenant Acting Professor of Chemistry and Mineralogy, 13 lieutenant assistant professors, and 12 teachers/instructors of tactics and foreign languages. Compare this academic staff of 30 with the 4 Professors and 8 other academicians that existed in 1818. As a group the Professors were outstanding in their fields and in several cases had written textbooks that were recognized as the best, or among the best, in the world. All the Permanent Professors had come from civilian life, but when on West Point they were considered Army lieutenant colonels and wore the uniform and had the privileges of that rank. Many of them served at West Point until their retirement or death. Their efforts, assisted by the lieutenant assistant professors and instructors/teachers, and the curriculum championed by Thayer graduated the engineers who would oversee most of the infrastructure construction that led to the settling of the United States. West Point was the only scientific and engineering school in the United States until Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute was founded more than two decades after West Point. Still, all courses aimed to support the engineering discipline. It was only in the senior Engineering course that Professor Dennis Mahan taught a few lessons about the tactics and strategies of warfare that guided both sides in the Civil War. For his sweeping changes, Thayer later became known as the “Father of the Military Academy.”

During the Civil War the performance of West Point graduates confirmed the value of their training and education but also revealed a weakness that would not be corrected for over 55 years. Of the 60 major Civil War battles, West Pointers commanded both sides in 55 of them. In the other five, a West Pointer commanded one side. However, their command was of an army of citizen-soldiers, and this fact revealed a significant weakness of the West Point experience. The close, fraternal relationship among West Point graduates did not sit well with the many more volunteer and Regular Army officers and enlisted men who were excluded from this inner circle. This, and lack of change to accommodate the lessons of the Civil War, observations from the Prussian War (1870–1871), as well as newer warfare technology, led to criticism of West Point between the end of the Civil War and World War I. What little change that did occur at West Point during this period was not initiated by the Permanent Professors comprising the majority of the Academic Board but rather by the Commandant of Cadets within his areas of tactical training and physical education. Again, in World War I, the Army leadership largely was made up of successful West Point graduates; however, the same issue of lack of empathy with the citizen-soldier arose. In addition, early graduations to support the war led to a chaotic situation in the Corps of Cadets. Colonel Douglas MacArthur, USMA Class of 1903, became Superintendent in 1919. Charged by the Army Chief of Staff to revitalize the institution, he strove to make sweeping changes.

MacArthur had observed the schism between West Point graduates and the citizen-soldiers, which became the vast majority of the Army as it mobilized quickly for World War I. He also observed the West Point graduates’ lack of preparation for the new tactics and technology employed during the war. When he became Superintendent, he immediately had to address the length of the program, which had been promised to be one year long for the Class of 1919 but was then extended, and post-war was set by Congress at three years. Under pressure from MacArthur, the Academic Board, and graduates, Congress relented and reauthorized the four-year program. This was one of the few times MacArthur had the support of the Academic Board. When he tried to make changes to the curriculum, he encountered strong resistance from the Permanent Professors who, by law, were the majority of the Academic Board and controlled the curriculum. By 1919 there were eight colonels and three lieutenant colonels serving as Department Heads and thus Permanent Professor members of the Academic Board. MacArthur brought about a few changes by convincing individual Professors to change their methodologies. The only changes agreed to by the Board were that Professors would visit three civilian institutions to observe and learn, instructors would spend their first year of assignment to the Academy at civilian institutions studying the subject they were to teach, more general lectures by men of authority and reputation would be given to the entire Corps, and a new combined course in Economics and Political Science (reduced from his request for four courses that included Psychology and Sociology) was created under a new Department of Economics, Government and History. The Professor in charge of the new department was directed to double the amount of time spent on his subjects and cover all social science subjects. These changes were designed to reduce the isolation that MacArthur saw as having the biggest impact on the ability of West Point graduates to command effectively. His observations and reading had led him to believe that adherence to old traditions at West Point had led to a huge disconnect between the cadets’ knowledge when they graduated and the mores of the society that shaped the citizen-soldiers that they would command. To further reduce this gap, he introduced the “whole man” concept that led to physical education being required for all classes and mandatory intramural sports for all cadets. He relocated the on-site summer encampment, which had become more of a social event than the training Thayer had intended, to Camp Dix, New Jersey, where the cadets underwent basic training with Regular Army troops. He also began granting significant privileges to cadets, allowing them to leave West Point on passes. The latter two changes were intended to provide cadets with opportunities to interact with the outside world. Due to the single furlough during the sophomore year instituted by Thayer, this interaction was lacking in their four-year experience. MacArthur’s intent was to produce graduates that would command respect and who understood the “mores and standards” of the men they would command (MacArthur, Reminiscences, 81).

MacArthur made three other significant changes. One was to implement a system to support the honor code instituted by Thayer. Second, he added evaluation of a cadet’s leadership, character, and physical performance (the “whole man”) to the order of merit. Third, he attempted to eliminate the practice of hazing the entering cadets by putting officers in charge rather than upperclassmen. This hazing, strongly supported by tradition, had reached such a level that it was blamed for a cadet suicide in 1919. The first two initiatives, modified by experience, continue in practice today at all military academies. Hazing, however, remains an issue to some degree for every Superintendent at every military academy to this day. Unfortunately, when MacArthur was reassigned in 1922 the next Superintendent restored the on-site summer encampment and cadet supervision of new cadet training. Subsequent superintendents embraced the MacArthur reforms and they were slowly implemented.

The years before and during World War II saw several changes that ultimately would have significant impact on the US Air Force Academy. The new Head of the Department of Economics, Government and History in 1930 was Colonel Herman Beukema, who would serve until 1954. His classmates in the USMA Class of 1915 included cadets Eisenhower, who would later become President, and Harmon, the first USAF Academy Superintendent. Beukema incorporated as much social science, taught in the context of war, into the curriculum as possible. The text he wrote on foreign governments also was adopted by numerous civilian institutions. Meanwhile in 1925 West Point was accredited as an “approved technological institution” by the Association of American Universities, and in 1933 Congress approved the granting of a Bachelor of Science degree to graduates. This made it easier for graduates to enter graduate schools to pursue advanced degrees. Also during this period, military “graduate” colleges such as the Army Command and Staff College (founded 1881), Army War College (1901), and the Army Industrial College (1924) taught the lessons learned in previous wars and expanded their curricula and improved their instruction. Thus, the stage was set for the United States’ entry into World War II. Coincidently, the West Point graduates who would form the majority of the new Air Force Academy faculty leadership were being educated in this system.

During World War II West Point graduates again were very visible in the top positions of the Army and generally demonstrated initiative, flexibility, and understanding of political affairs. However, West Pointers did not dominate command positions as they had previously, largely due to the education and training provided Regular Army officers in the military graduate schools. Of the commanders at division-level or above, 57 percent were USMA graduates chosen from the 41 percent of the Regular Army officers who were grads. After the war, General Maxwell D. Taylor became the Superintendent and made many changes brought about by advances in technology and the lessons of the war. He was helped by an Act of Congress, dated June 26, 1946, that added nine Permanent Professors who would serve in each of the nine departments already authorized a Permanent Professor Department Head, established the position of Professor of Law and the Professor of Ordnance as Permanent Professors, and provided an additional Permanent Professor as Dean of the Academic Board. The Dean was to be appointed from among the Permanent Professors who had served as heads of departments, and the Dean of the Academic Board would have the rank, pay, allowances, retirement rights, and other benefits authorized for permanent brigadier generals. These Permanent Professor authorizations would still be in effect in 1954 and apply to the Air Force Academy when it was established. The new Permanent Professors proved to be ardent proponents of the principals MacArthur had introduced. One of these new Professors had become a brigadier general in the war, but he returned to West Point as a colonel to serve with Colonel Beukema. Fencing and Horsemanship were dropped; Nuclear Physics, Electronics, Communications, Russian and US History, International Economics, and Psychology were among the courses added. In 1948 the First Classmen were tested against 1,174 men from 41 liberal arts colleges using the General Education Test of the College Record Examination. The West Point men’s average index score was 589 compared to the liberal arts seniors’ 523. The cadets scored better in five subject areas, falling below the others only in fine arts and biological science, neither of which was taught at West Point. Clearly West Point had recaptured its position as one of America’s better universities. Even though in 1964 the curriculum still was prescriptive with no electives, the practice of sectioning classes by ability allowed a formal Advanced Academic Program with more than 20 advanced courses for the more capable cadets.

The foregoing evolutionary history of the USMA sets the stage for understanding the new United States Air Force Academy, because the planning (1948–1954), the initial staffing (1954–1955), and the education and training of the first class to graduate (1955–1959) were led by officers who were predominately USMA graduates or who had taught there.

Early Leadership Sets the Tone

The early senior leaders of the Air Force Academy were nearly all graduates of the United States Military Academy. The Superintendent, Lieutenant General Herbert H. Harmon, graduated from the USMA in 1915 and returned as an instructor, 1929–1932. He commanded flight training units, 1940–1942, and was the Special Assistant for Air Academy Matters, from December 1948 until assuming command of the USAFA in August 1954. General Harmon recognized the importance of getting key personnel identified and assigned. He had asked for appointment of a Dean of the Faculty and Commandant of Cadets as early as October 1951 and repeated this request several times. When General Harmon assumed command of the USAFA, he did so from the single room available to the seven Academy personnel present for duty at Lowry AFB and with only one senior leader among them, the Dean of the Faculty, Brigadier General Don Z. Zimmerman, who had been appointed July 22, 1954.

General Zimmerman had an impressive record. He had earned Bachelor’s and Master’s degrees, and a commission as a second lieutenant in the US Army Reserve prior to graduating from West Point sixth in a class of 299 in 1929. After flying duty, he earned a Master’s degree in Engineering (Meteorology) from the California Institute of Technology in 1936. He then instructed Air Corps Primary Flying for four years and wrote the Weather Manual for Pilots used throughout the Air Corps and US Army. He returned to West Point in 1940 and taught Mathematics for the fall semester. Due to the war in Europe, he spent nearly a year studying long-range weather forecasting, and in early 1942 he was appointed Director of Weather for the Army Air Forces and the US Army. During the Korean War, he served in staff positions in HQ Far East Air Forces and was promoted to brigadier general. While General Zimmerman’s military credentials and academic achievements as a student were impressive, General Harmon had reservations about his lack of academic teaching and administrative experience.

At a 1954 White House dinner with his West Point Class of 1915 classmates (President Eisenhower, General Omar Bradley, and others), General Harmon expressed his concerns. Retired Colonel Beukema recommended that Harmon consider Colonel Robert F. McDermott, currently teaching in the Social Sciences Department at West Point, to be the Professor of Economics and Vice Dean of the Faculty. Colonel Beukema as the Professor and Head of Social Sciences at West Point had been very impressed by McDermott. Within a few days, General Harmon was interviewing Colonel McDermott in the latter’s office at West Point. General Harmon offered Colonel McDermott the two positions, but McDermott turned him down, saying that he wanted to return to flying. When Harmon became more persuasive, McDermott did not waiver and told Harmon that he couldn’t be assigned to the Air Force Academy because he had orders to Japan with a port call in fewer than 30 days. (Air Force regulations at the time did not allow changes to orders under those circumstances.) The next day McDermott received orders canceling his Japan orders and assigning him to the Air Force Academy as Professor of Economics. This assignment, brought about by the traditional close bond among West Point classmates, would prove pivotal in the development of the Air Force Academy as McDermott would later be dubbed the “Father of Modern Military Education.” Colonel McDermott arrived at Lowry AFB on October 18, 1954, as Professor of Economics and became Vice Dean as an additional duty on November 12, 1954. He had attended Norwich College for two years before entering the USMA, graduating in 1943. After flying combat in Europe during World War II, he served as a Personnel Staff Officer, 1945–1948. He earned a Master’s degree in Business Administration from Harvard University in 1950. He then served as an Instructor in the Department of Social Studies at the USMA until his departure for Lowry.

To lead the Academy’s military training General Harmon chose Colonel Robert M. Stillman, who was appointed Commandant of Cadets on September 1, 1954. Colonel Stillman attended Colorado College in Colorado Springs on a football scholarship for two years before entering the USMA and graduating in 1935. For the next three years, he returned to West Point each fall as a member of the football coaching staff. He participated in two low-level B-26 bombing missions over Europe, being shot down on his second one. Captured in Holland May 17, 1943, he remained a prisoner of war until April 29, 1945. While serving in the Pentagon as Chief of Officers’ Assignments, he became involved in Academy planning, working with General Harmon. General Stillman chose all of his senior staff from the ranks of West Point graduates, and they set out to implement a training system closely modeled on the Military Academy’s methods. The Commandant was responsible for military, flying, and physical training until the Department of Physical Education was transferred to the Director of Athletics in 1959. One of Colonel Stillman’s first actions that has endured was to request a change in the military organization of the cadets. The planning had stipulated an air division with two wings, three groups per wing, with six squadrons in each group. Feeling this was administratively awkward and unnecessarily complicated, Stillman proposed a single cadet wing with squadrons of 100 men organized into 6 groups to form the wing. His proposal was approved and evolved to the current cadet wing organization of 4 groups and 40 squadrons.

The Athletic Director, Colonel Robert V. Whitlow, was appointed on June 29, 1954. He was an excellent golfer and, while stationed at HQ Air Defense Command in Colorado Springs, had played golf with local and Pentagon Generals and other officials including soon-to-become Secretary of the Air Force Talbott, General Harmon, General O’Donnell (AF Deputy Chief of Staff, Personnel), and even President Eisenhower. Graduating from the USMA in 1943, he had won letters in football, basketball, and track. Before entering West Point he had played football for three years at UCLA. A very enthusiastic sportsman, he attacked every task with zeal and scheduled the Academy’s first football game with the University of Denver for October 8, 1955, fewer than three months after the first cadets reported for duty on July 11, 1955. With strong support from Secretary Talbott and General O’Donnell, he continued to promote intercollegiate sports vigorously, especially football. This led to conflicts with academics, concerns about accreditation, and even conflicts with the USMA’s recruiting of athletes. He brought in as his assistant Major Frank Merritt, who served as assistant football coach and would later become the Director of Athletics.

During site selection (April–June 1954), General Harmon’s staff prepared lists of qualified individuals for his review. Emphasizing the importance of this task was the requirement by Secretary of the Air Force Talbott that he must approve General Harmon’s selections. After Harmon, with the assistance of the AF Deputy Chief of Staff, Personnel, and the AF Chief of Staff, obtained approval for key faculty and staff positions, the Secretary removed this restriction in August 1954. General Harmon then decided that he would let his leaders (Dean, Commandant, Athletic Director) choose their own personnel using guidelines that had been established by the Air Force Academy Planning Board Report in 1949 and refined since. Selection criteria to guide Professors as they selected their faculty were formalized in October 1954 by the Dean of the Faculty.

By the end of October 1954, eight professors, the librarian, and the Assistant Dean of the Faculty/Director of Audio-Visual and Training Aids, Service Training, and Examination had reported for duty at Lowry. The latter, Colonel Arthur E. Boudreau, was a USMA graduate and had been recalled to active duty in 1948 from his position as Dean of the Inter-American College, Coral Gables, FL. He had chaired the Curriculum Committee of the Air Academy Planning Group at Maxwell AFB before becoming General Harmon’s Executive Officer on his Pentagon staff; he also had played a key role in the selection of the final Academy site. These early selections were exceptionally well-qualified and are shown below, along with two lieutenant colonels who played early key roles developing the required freshman courses. Lieutenant Colonel Woodyard would become the Professor of Chemistry in August 1955, and Lieutenant Colonel Sullivan would develop a new Philosophy course before being replaced by Colonel Thomas L. Chrystal, Professor of Philosophy, in July 1955. Chrystal was a 1934 USMA graduate with a Master of Arts degree from Columbia University and had taught at the USMA for five years.

| Name | Date Reported (1954) | Position | Education | Years Teaching Experience |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Col Arthur E. Boudreau | 27 Sep | Assistant Dean of the Faculty | MA | Administrator |

| Col Peter R. Moody | 27 Sep | Prof of English | BA, Wofford College USMA 1942 MA, Duke | 5, USMA |

| Col James V.G. Wilson | 30 Sep | Prof of Chemistry & Physics | USMA 1935 MS, Illinois | 6, USMA |

| Lt Col Arthur J. Larsen | 30 Sep | Director of Library | BS, MA, PhD, Minnesota | 10, Minnesota |

| Col Allen W. Rigsby | 11 Oct | Prof of Law Staff Judge Advocate | BA, Law, Oklahoma | None |

| Col Archie Higdon | 14 Oct | Prof of Mathematics | BS, South Dakota State MS, PhD, Iowa State | 12, Iowa State 3, USMA |

| Col Josephus W. Bowman | 14 Oct | Prof of Geography | USMA 1939 MPA, Harvard | 3, USMA |

| Col Robert F. McDermott | 18 Oct | Prof of Economics | USMA 1943 MBA, Harvard | 4, USMA |

| Col John L. Frisbee | 18 Oct | Prof of History | BA, Hartwich MA, Georgetown | 3, USMA |

| Col James S. Barko | 18 Oct | Prof of Engineering Drawing | USMA 1937 MS, Cornell | None |

| Lt Col William T. Woodyard | Oct | Assoc Prof of Chemistry | BS, MS, Missouri | 3, USMA |

| Lt Col Cornelius D. Sullivan | 20 Nov | Acting Prof of Philosophy | BA, MA, Toronto | (unknown) |

Of the men listed above, five (Moody, Wilson, Higdon, McDermott, and Woodyard) would later be appointed Permanent Professors. It should be noted that since the appropriate provisions of the laws pertaining to West Point were to apply to the Air Force Academy (Section 5 of the April 1, 1954, law), 21 Permanent Professors were expected to be authorized. Hence, there was an implied tenure to the Professors’ appointments, but no procedures were yet in place to nominate the appointment of Permanent Professors.

Using the selection criteria promulgated by General Zimmerman, the Professors, aided by a HQ USAF Selection Board, selected 55 instructors for assignment to the Academy by November 8, 1954. A similar process would be followed each year until the cadet wing reached its authorized strength and the faculty was fully staffed. The table below presents the military and educational characteristics of the initial cadre of officers, compared with the percentage goals that had evolved by 1955.

| Characteristic | Actual Percent | 1955 Goal Percent |

|---|---|---|

| USMA Graduates | 33 | At least 25 |

| Regular Officers | 56 | At least 50 |

| Reserve Officers | 42 | |

| Rated Officers | 53 | At least 60 |

| Non-Rated Officers | 47 | |

| BS Degrees | 17 | 0 |

| MA/MS Degrees | 67 | |

| PhD Degrees | 16 |

The faculty was now on board to prepare for the freshman classes and equip the laboratories for academics to begin in September 1955, only 10 months away. Lurking in the background was the second priority, to obtain accreditation prior to the graduation of the first class in 1959. Application of the laws governing the USMA again came into play. Since the USMA and the US Naval Academy were not authorized to grant degrees without accreditation, it was assumed a like condition would be imposed on the Air Force Academy. Further adding to the pressure was the Academy Catalog published in 1954, which stated that a Bachelor of Science degree would be awarded graduates.

The initial de facto organization of the faculty was aligned under the professors of the core curriculum disciplines. For the first year these disciplines (courses) were Chemistry, English, Graphics, History, Mathematics, Philosophy (logic), Geography, and Physical Training. Physical Training and its spring semester replacement, Airmanship, were taught under the Commandant of Cadets. On November 12, 1954, the Dean created a Faculty “Committee of the Whole” composed of the professors and assigned them the task of addressing the roles and responsibilities of the faculty. The Dean also established three sub-committees: the Scientific Studies Committee, the Social Sciences Committee, and the Humanities Committee. On September 1, 1954, the Special Assistant for Air Academy Affairs Curriculum Planning Group had published a report entitled Air Force Academy Program of Instruction, which contained detailed course syllabi for each course in the prescribed curriculum. But General Zimmerman told the Committee of the Whole that they were to consider three issues: the freshman curriculum, the four-year curriculum, and the freshman schedule, suggesting that the planned curriculum was subject to modification. To review items of general concern to the entire faculty, the Dean established three more committees to consider such items as grading, elimination of cadets for deficiencies, cadet academic awards, homework assignments, curricula and schedules for the three upper classes, classroom furniture, improving faculty education opportunities, and faculty and department organization, to name a few. To implement and guide this interim committee organization, General Zimmerman appointed Colonel McDermott to be the Vice Dean of the Faculty.

Meanwhile, the Dean continued to work with the individual professors as they refined the goals, objectives, and syllabi of the freshman courses. Work was also underway to determine textbooks that might be used and the long lead tasks of specifying and obtaining classroom and specialized laboratory equipment for Chemistry, Graphics, Physics, and Engineering. The Dean also directed the faculty through a series of policy letters, which among other things guided faculty behavior in staff meetings, assigned responsibilities to the different academic ranks, established procedures for extra instruction given to cadets outside of the classroom, and established expectations for faculty participation in professional meetings to maintain currency in their disciplines. In September 1955, the Dean established a Freshman Committee with responsibility for continuously reviewing the freshman curriculum in order to improve it both for the current and subsequent years. As all these committees and the professors brought their recommendations to the Dean for his approval, or to forward to the Superintendent as appropriate, the formation of the faculty, the curriculum, and the cadet schedule took place. During his many years working toward the Academy’s establishment, General Harmon had formed a clear, detailed vision of what the Academy should be and how it should operate. Therefore, he was intimately involved in decisions regarding the curriculum, the cadet schedule, and the selection and education of faculty. As items for decision were debated before him, the Superintendent was increasingly impressed with the depth of knowledge and articulate arguments made by the professors, which generally overwhelmed those of the Commandant and Athletic Director.

During this formative period three professors became most influential in the decision-making process. Colonel Moody was an articulate advocate for the humanities and social sciences and Colonel Higdon had equally strong arguments in favor of the sciences; they debated their cases eloquently when conflicts for time in the curriculum arose. As the Vice Dean and Secretary of the Committee of the Whole, Colonel McDermott had the responsibility of submitting all recommendations, so he, within reason, could shape the arguments, try to sway recalcitrant Professors, and determine the way items were presented to the Dean and Superintendent for decisions. Colonel McDermott welcomed informed debate but was strongly focused on developing a balanced curriculum producing “whole man” graduates capable of academic statesmanship and dynamic, inspired leadership. He was a formidable, well-prepared foe in arguments with those holding different views. This was demonstrated in late 1954 during the first meeting to consider admission criteria for the new class. As usual, McDermott had prepared well and presented a detailed list of desired attributes. Colonel Whitlow quickly recognized that many of the athletes he was trying to recruit could not meet McDermott’s criteria, so he proposed a method of granting exceptions for special cases. The argument became so heated that the Dean ordered Colonel McDermott to remain in the Dean’s office in the afternoon, so the admissions process could continue without him. Incensed, McDermott asked the Superintendent to overrule the Dean, but General Harmon declined to do so. Perhaps part of his reason for upholding the Dean may have been the openly stated view of the Secretary of the Air Force and the DCS for Personnel, General O’Donnell, that the best publicity the Air Force Academy could obtain was to have a winning football team. This focus later became an issue when Colonel McDermott arranged a visit by Andrew M. Patillo, Jr., a consultant to the North Central Association of Colleges and Secondary Schools, which was the accrediting body for the Academy. Gaining accreditation in time for the Class of 1959 was to be a real challenge, as accreditation was not normally granted until at least a full four years of instruction had been demonstrated.

General Harmon’s original misgivings about General Zimmerman’s academic administrative experience had been borne out as the Dean tried to impose his own narrow view on the focus of the curriculum, became bogged down in detail and slow to make decisions, and failed to impress visitors from the North Central Association, which was to evaluate the Academy for accreditation. These factors led to his reassignment on December 1, 1955. General Harmon assumed the additional duty as Dean of the Faculty and McDermott, as Vice Dean and Secretary to the Committee of the Whole, became the Superintendent’s conduit to the faculty. Fortuitously, Economics was to be a junior year course, so McDermott was not pressed to spend time developing it. A review of all critical faculty matters was quickly ordered by the Superintendent. The resulting report, largely reflecting Colonel McDermott’s views, recommended establishing a faculty senate composed of the Dean and all professors. Implemented on December 15, 1955, as the Academic Policy Board, this body later became the Faculty Council with membership to include all Department Heads (who may not have been a Permanent Professor, due to sabbatical assignments or vacancies), which to this day considers all things faculty-related and makes recommendations to the Dean, or through the Dean, to the Superintendent or the Academy Board.

Another way that the professors influenced Academy decisions was through membership on the Academy Board. Early staff meetings held by General Harmon at Lowry AFB included the professors, Dean, Director of Athletics, Commandant, Director of Flying Instruction, Director of Physical Training, and the Director of Military Instruction. This body began calling themselves the “Academic Board” after the governing body at West Point. However, they soon realized the USAFA group had more non-academic members than did West Point’s, so the name changed to the “Academy Board.” This informal Board became an organizational reality in August 1955, when, after considering a proposal from Colonel McDermott, the Superintendent formed an Academy Board consisting of himself, the Dean, the Commandant, five Professors, and the three directors of instruction under the Commandant. This Board was to recommend men for appointment as cadets by the Secretary of the Air Force, consider cadet disenrollment actions, and perform other duties assigned by the Superintendent. However, it was not to consider academic matters or admission criteria. HQ USAF officially recognized the Air Force Academy Board in January 1956 to consist of the Superintendent, Dean, Commandant, and heads of academic and airmanship departments as appointed by the Superintendent, with the Registrar to be the non-voting Secretary. The Academy Board was reorganized in March 1956, when General Harmon was both the Superintendent and the Dean, by deleting the Superintendent and adding one professor. While patterned after the Academic Board at West Point, the USAFA Academy Board had a much broader scope, more non-academic representation, and less power over the curriculum. By default, the curriculum decisions reverted to the Faculty Council, sitting as a Curriculum Committee. In August 1956, when General Briggs became Superintendent in August 1956, he revised the Board’s role again; now the Board would be the decision authority for curriculum and related matters and the Faculty Council would make recommendations on these subjects.

Changes in Academy leadership continued after General Zimmerman’s departure. Major General James E. Briggs had been identified by the AF Chief of Staff to replace General Harmon, who planned to retire in the summer of 1956. General Briggs graduated from the USMA in the Class of 1928, holding the highest cadet rank. He had returned to West Point as a member of the Mathematics faculty, 1940–1942. During World War II and the Korean War, he held numerous operational flying and staff positions. He gained invaluable insight into the Academy as Chairman of the USAF Academy Curriculum Review Board that convened in February 1956. The Board was established by the AF Chief of Staff at General Harmon’s request to examine the current curriculum and either approve it or suggest changes. Feeling the cadet workload was too heavy, a view shared by the Commandant and Director of Athletics, Colonel McDermott had tried unsuccessfully to get the Faculty Council to reduce the workload. Each Professor was unwilling to give up any cadet time devoted to his discipline. McDermott was now in a position to push for changes he thought were required. The Curriculum Review Board recommended a reduction in workload, agreed with McDermott’s proposed reorganization of the faculty into departments grouped into divisions according to academic disciplines, more faculty teacher training, and replacing the Academy Board with an Academic Board modeled after the USMA’s. The Superintendent agreed with all recommendations except the last one, which he felt was unnecessary because the faculty already held a majority membership on the Board.

General Harmon’s intense desire to get everything right about his new Academy presented a very heavy workload: making the unending decisions involved in developing processes and overseeing day-to-day operations, guiding the design for the permanent site, and ensuring favorable public affairs and relations with Congress to enhance the Academy’s reputation and keep funding flowing. This workload had taken its toll. In May 1956 he was diagnosed with advanced cancer. General Brigg’s arrival at the Academy was moved forward to June 1956, and he became the Assistant Superintendent to relieve Harmon’s workload. In one of his first meetings after reporting to the Academy, General Briggs told Colonel McDermott that he was to become Superintendent on August 1 and intended to appoint McDermott as Dean of the Faculty. Soon McDermott sent a memorandum to Briggs recommending Permanent Professors be appointed to ensure stability, integration, continuity, and evolution of the instructional program. Briggs agreed and started his own search for the best qualified individuals, but he would not recommend anyone for another seven months. In a second memorandum, McDermott laid out his views on the functions, title, duties, and relationships of the Dean. He felt the Dean should have overarching control of the curriculum. Further, he argued the Dean should be able to nominate Permanent Professors, should write their effectiveness reports (being written by the Superintendent at that time), and should be the authority to select and relieve all faculty members. During this turbulent summer an attempt to have the Dean, Commandant, and Director of Athletics report to the Academy Chief of Staff rather than the Superintendent was successfully thwarted by General Briggs’s rejection of the proposal after he became Superintendent.

A critical factor in the accreditation of an institute of higher learning is its library. In early 1956 it became clear that the Air Force would not extend Lieutenant Colonel Larsen, who had done an outstanding job establishing the library, beyond his mandatory retirement date. A curriculum change for Academic Year 1956–1957 had moved American History to the junior year, making the American History course chairman, Lieutenant Colonel George V. Fagan, available for other duties. A PhD in History with teaching experience at Temple University and the USNA, Fagan had been actively recommending books for the library’s collections. General Harmon appointed Fagan the Acting Director of the Library effective June 1, 1956. Thus began his exemplary service in that post for the next 13 years, the last 6 as a Permanent Professor. The only Permanent Professor to never head a department, Fagan played a significant role in the design of the permanent site library and the early accreditation of the academic program.

In August 1956 the Academy Board approved McDermott’s proposed faculty organization of equal numbers of related departments organized into divisions representing Humanities, Social Sciences, Basic Sciences, and Engineering Sciences (see following chapters). He then turned his attention to achieving accreditation and providing academic enrichment opportunities for deserving cadets. While a cadet at West Point, McDermott had very much disliked repeating courses that he had previously mastered during his prior two years at Norwich College. The appeal of attending the new Air Force Academy and learning to fly was bringing in many cadets with prior college experience who were suffering the same frustration with the prescribed, inflexible curriculum. Colonel Higdon had already experimented with a voluntary accelerated course in math during the first year. Over 100 cadets had participated with 35 completing three extra courses for five extra credit hours. In the fall semester of 1956, voluntary enrollments in accelerated courses in Math, Chemistry, English, and Graphics numbered 268 cadets. That December, McDermott proposed his enrichment program to the Professors: cadets would receive validation credit for courses they had previously taken at civilian colleges that were equivalent to those prescribed in the curriculum (these cadets could take elective courses instead), gifted cadets could take extra courses, and the social sciences/humanities course offerings would be expanded to broaden knowledge and extra science courses provided to deepen knowledge. This break with the tradition of a prescribed curriculum for all at West Point and Annapolis would lead in 1958 to the approval of majors in Basic Science, Engineering Sciences, English, Western Culture, and Public Affairs. Later that year even more flexibility was granted a cadet with a concentration of 17 semester hours or more in an area, allowing him to graduate with a major developed with a department or division and approved by the Faculty Council and the Dean. In the Class of 1959, over 10 percent of the class earned a major and over 29 percent of the Class of 1960 did so.

Accreditation was still an issue that had to be addressed. Through numerous visits to the North Central Association beginning in February 1955, Mc Dermott and others learned the process and guidelines for accreditation and developed strategies to overcome the deficiencies they expected accreditors to uncover. Although the curriculum had been developed closely aligned with that of West Point, the original planners, and later the Professors, had invited numerous reviews of their work by outside civilian experts. These resulted in many refinements and a deeper understanding of the civilian education system and accreditation challenges. This was in sharp contrast to the isolationism that had prevailed at West Point prior to MacArthur and that still lingered there. In the summer of 1957, Colonel McDermott put Colonel Woodyard, his teaching colleague and next-door neighbor at West Point, in charge of the accreditation effort. Woodyard had proven himself as Professor and Head of the Chemistry Department. The Superintendent established the USAFA Accreditation Committee with Woodyard as chairman and included members of the Superintendent’s and Commandant’s staffs. Working full time, Woodyard identified concerns about faculty tenure, faculty academic qualifications, and faculty participation in academic decision-making, among others. The work of 20 committees culminated in June 1958 when the Self-Study Report was flown to Chicago in a T-33 aircraft by Woodyard. This preparation for accreditation, begun in the early planning for the Academy, ended successfully with the very unusual accreditation of the Academy in April 1959 before its first class had graduated.

One of the concerns raised in the accreditation review was that of faculty tenure. Applying the laws governing the USMA as directed in the 1954 act, the USAF Judge Advocate General had ruled that the provisions for Permanent Professor appointments were applicable to the Air Force Academy. In February 1957, General Briggs sent Colonel McDermott’s nomination package to the Air Staff, recommending his appointment as Permanent Professor (but not Permanent Dean, which would carry with it promotion to brigadier general). Included were recommended policies for the selection of the Permanent Professors, retention on flying status, and adjustment in McDermott’s date of rank as a colonel. Extensive delays ensued as the Air Staff wrestled with this landmark decision. Thinking the cost of retaining flying status was the issue, General Briggs wrote a long letter explaining his rationale for this request. Finally, on October 16, 1957, the Secretary of the Air Force approved Colonel McDermott as the first Permanent Professor and approved retaining him and future Professors on flying status. Using the rationale that McDermott was no longer on the Line of the Air Force promotion list, the change in his date of rank as a colonel to August 15, 1943, also was approved. This date, fewer than six months after he graduated from West Point, was sufficiently early to ensure he outranked the most senior colonel on the faculty. Colonel McDermott would be nominated for Dean by the Superintendent, Major General Briggs, on May 16, 1959, and the Secretary of the Air Force forwarded his nomination on August 27. The President approved, and the Senate confirmed his appointment as permanent Dean and promotion to brigadier general effective September 15, 1959.

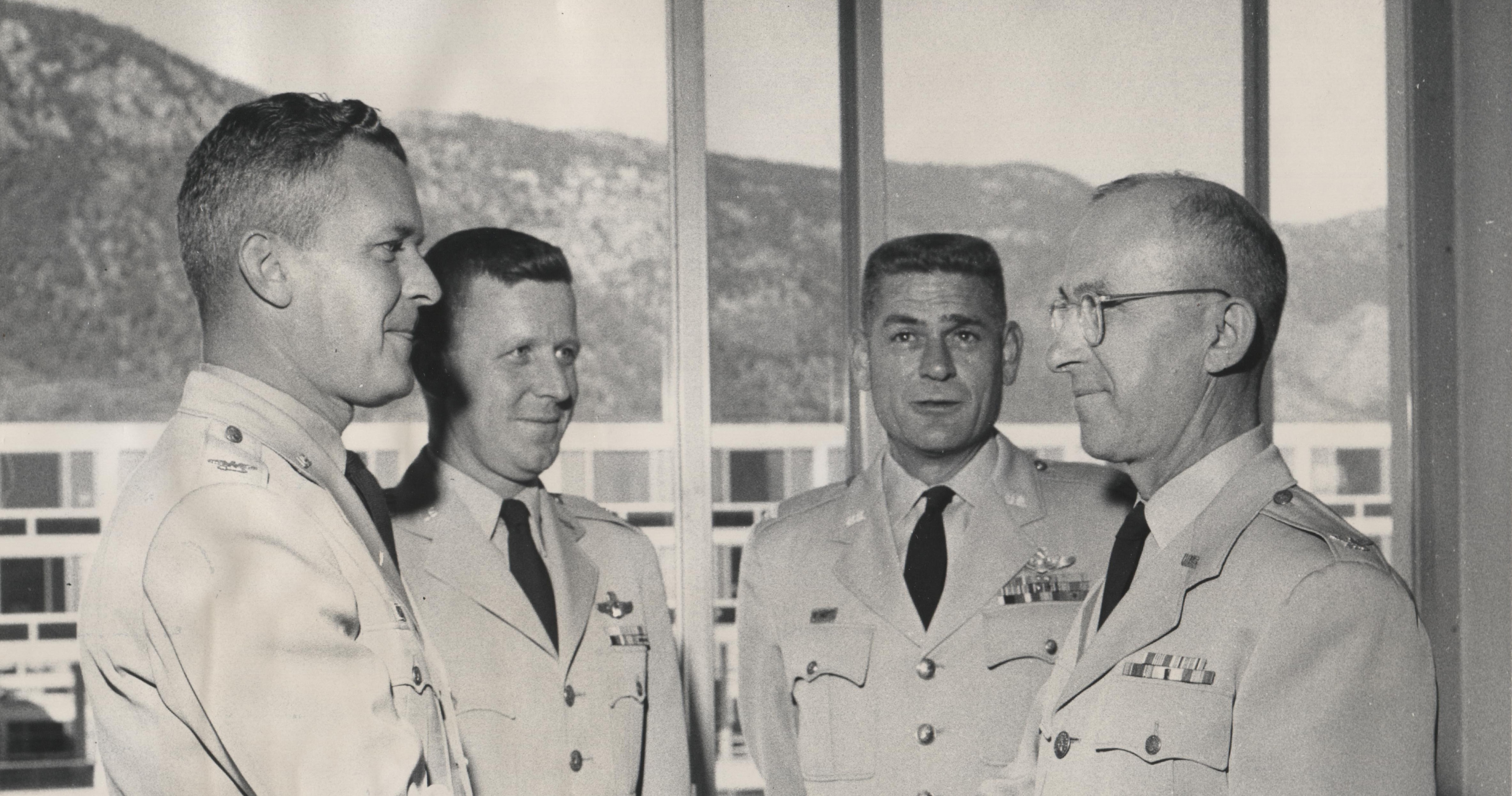

The next three Permanent Professors, Colonels Woodyard, Moody, and Higdon, were appointed in 1958. This photograph, from that year, shows these first four Permanent Professors (from left, Colonels McDermott, Woodyard, Moody, and Higdon). The scene is a familiar one, from the Dean’s office in Fairchild Hall overlooking the terrazzo to Harmon Hall and the Rampart Range beyond.

The next three Permanent Professors, Colonels Woodyard, Moody, and Higdon, were appointed in 1958. This photograph, from that year, shows these first four Permanent Professors (from left, Colonels McDermott, Woodyard, Moody, and Higdon). The scene is a familiar one, from the Dean’s office in Fairchild Hall overlooking the terrazzo to Harmon Hall and the Rampart Range beyond.

These four members of the initial cadre, who had worked so hard to make the new USAF Academy successful, saw their contributions and potential for further progress recognized. They would be the first to admit they had not accomplished this monumental task by themselves; the enthusiasm, hard work, and dedication of the other leaders and personnel assigned to the faculty as well as other Academy organizations certainly had done their share. As history would show, the innovative changes undertaken by these early Academy leaders would soon cause a revolution in military education at the other US military academies.